New cancer immunotherapies that recognize and attack specific cancer cells are extremely effective for some patients but come with a high risk of life-threatening immunotoxicities.

To help refine immunotherapy safety and predictability, a team of researchers from Vanderbilt University Medical Center and GE Healthcare have developed an artificial intelligence (AI) model using machine learning to develop risk-benefit profiles of various immunotherapy types.

Findings from a recent trial run of the model, reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology Clinical Cancer Informatics, had 70 to 80 percent accurate performance in its predictions for cancer immunotherapies. The AI model was designed to evaluate real-world patient data collected from routine electronic health records (EHRs).

“Understanding who is most likely to benefit from immunotherapy and who is most likely to have side effects would really be transformative in how we deliver care with immunotherapy drugs.”

“Understanding who is most likely to benefit from immunotherapy and who is most likely to have side effects would really be transformative in how we deliver care with immunotherapy drugs,” says Travis Osterman, D.O., associate vice president for research informatics at Vanderbilt and senior researcher on the study.

Immunotherapy

Most existing methods for predicting toxicity or effectiveness are not practical in clinical settings, the authors noted, because they require data not routinely collected and that is difficult to extrapolate to larger cohorts.

This study stood out from existing research in two key ways, Osterman said.

“First, we did not limit ourselves to a single tumor type, which meant anyone who received any of these drugs at Vanderbilt could be included in the in the retrospective deidentified study,” he said. “Second, the data that we used – from the EHR – is readily available in the vast majority of oncology practices in the United States.”

The machine-learning algorithm they developed is a form of AI that can find patterns in datasets and draw independent conclusions. The researchers provided classifications for potential negative outcomes among patients at the start of immunotherapy for hepatitis, colitis and pneumonitis, and the rate of survival for at least one year.

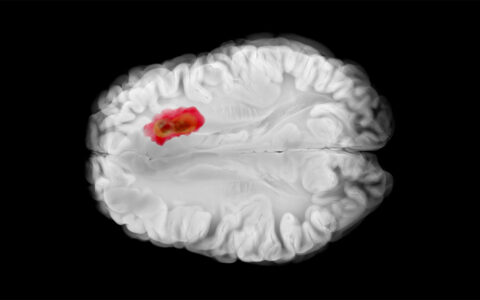

While the AI models only evaluated clinical data, the researchers also collected data from images of tumors for future research.

“The data that we used from the electronic health record (EHR) is readily available in the vast majority of oncology practices in the United States.”

This study was fueled EHR data from 2,230 patients treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors over 10 years. The patient cohort had a median age of 63 and was 61.8 percent male. While the study was not limited to a specific type of tumor, the predominant cancers were melanoma, lung cancer and genitourinary cancers.

The models demonstrated strong performance, with areas under the curve between 0.729 and 0.755 for the four prediction outcomes.

Looking Ahead

The team-based research stems from a collaboration that developed between GE Healthcare and VUMC more than five years ago. With this study, GE Healthcare provided support to scale and commercialize the research, while Vanderbilt provided the patient data and expert guidance for parameters of the AI model.

The next step for researchers is to validate the AI models with datasets from other health systems and countries.

“The goal of this study was to use standard data and make the AI model as flexible as possible to adapt to other health care settings,” Osterman said. “We did not want to overfit the AI model to a localized environment.”

In a promising trial validation, two of the four outcome models created for the study have been validated externally with data from a health care system in Essen, Germany, Osterman said. The AI models retained around 85 percent of their performance with this very different clinical population, he said.

The current study evaluated the data retrospectively, but moving forward, researchers hope to use their models to evaluate toxicity and effectiveness of immunotherapies prospectively, to see if the three toxicities evaluated (hepatitis, colitis, and pneumonitis) “match in a prospective manner what we’ve developed in a retrospective way,” says Osterman.

These findings have the potential to contribute to safer clinical care by tailoring treatments more precisely to each patient’s risk profile.