Patients with heart failure commonly are hospitalized with lung congestion and associated shortness of breath, yet no consistent, successful approach to treating the condition has emerged.

This fact underlies an ongoing trial to examine the rigorous use of urine chemistry measurements to guide the prescription of diuretics in contrast with the usual-care model for achieving decongestion in heart failure patients.

“Historically, we do a very bad job of monitoring response and making timely adjustments in the IV diuretics we use,” said Zachary Cox, Pharm.D., an adjunct professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and a site investigator in the trial.

“Historically, we do a very bad job of monitoring response and making timely adjustments in the IV diuretics we use.”

“The body adapts quickly to the drugs and changes how much excess fluid it eliminates via urination. We are cat-and-mousing the body on this. The two big issues we are trying to address are bad diuretic response data and how quickly we respond to the data.” Appropriate diuretic dosing can vary greatly across patients, and even for the same patient over a stretch of time, Cox explained. For some patients, a doctor will need to prescribe 10 or 20 times the amount of medicine normally called for as they develop diuretic resistance.

Randomized, Controlled Trial

The study, conducted by Cox and principal investigator Sean Collins, M.D., a professor of emergency medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, along with researchers at Yale University School of Medicine and the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, will involve at least 450 adult subjects admitted to a hospital for acute decompensated heart failure.

“Over the last decade, urine chemistry has been evaluated as a guide to deliver diuretic therapy for patients with heart failure,” Collins said. “Our strategy trial builds on this idea by using two urine chemistry measures to identify patients who are not responding to therapy. These tests are inexpensive and readily available to providers across the world. Thus, if the study suggests an advantage to our strategy, this approach can be implemented rapidly in most hospitals.”

After participants are randomized to the intervention arm or the usual-care arm, they will all receive an initial dose of an IV diuretic. The trial began in May 2022 and the researchers hope to complete enrollment in 2026.

In the usual-care arm, the clinical team will adjust frequency and intensity of the diuretic dosing based on the patient’s response.

“The clinical team can increase or decrease the dose of diuretics according to routinely measured diuretic response variables, such as weight change, physical exam and net fluid input-output.”

They will specifically measure two factors.

To gather the first, investigators are asking patients to rank how much better they feel after treatment on a scale of one to 100, Cox said. For No. 2, they will determine whether the new approach leads to patients being alive and out of the hospital for more or fewer days during the 14 days post-enrollment.

Finely Tuned Approach

In the intervention arm, the new strategy being tested is called urine chemistry-guided diuresis. With this strategy, each patient’s physician sets a goal for the amount of fluid and sodium to be excreted by the patient.

The researchers devised an equation, which they call the natriuretic response prediction equation, to reliably estimate how much sodium a patient will excrete in urine after taking a prescribed diuretic.

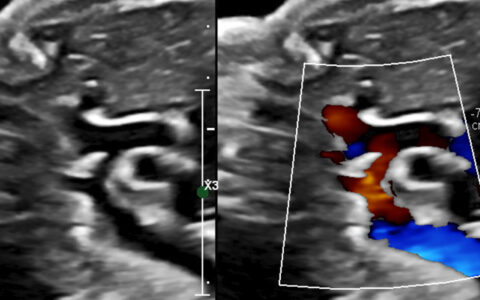

Two hours after the first dose, testing determines the sodium and creatine levels in the patients’ urine.

“Knowing those levels and using a couple of other easy parameters – such as weight, height, and age – we can use the equation to accurately predict how much sodium they will urinate over the time that the medicine is working,” Cox said.

They will be asking whether the patient’s response is “good or bad, relative to what the physician said that they wanted. We are monitoring their progress toward the goal.”

For patients making progress, the dose is left unchanged. If they are not, the dose is doubled.

Cox said the urine chemistry testing and calculation occur after every dose, up to three times a day.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is providing funding for the trial. It is considered the largest randomized, double-blind trial to study a diuretic strategy using urine chemistry.

Lower Cost Approach

In the Medicare population, heart failure is the number one cause of hospitalization, Cox said.

“The existing literature says that patients who are not urinating out enough sodium have bad outcomes. They return more often to the hospital, and they’re at higher risk of dying.”

One 2022 estimate of the costs for heart-failure hospitalizations in the United States found that average heart-failure-specific costs per inpatient ranged from $10,737 to $17,830. In the U.S., this would add up to $18 billion in hospitalization expenses for the condition.

“It’s not an expensive new drug. You use your same drugs differently and better.”

“If this strategy works, it will have enormous benefits,” Cox said. “From the patient’s perspective, expediting their discharge from the hospital by improving decongestion efficiency has a lot of benefits.”

From the perspective of the hospital system or clinician, hospital stays may be reduced and readmissions may fall, he says.

“It’s not an expensive new drug. You use your same drugs differently and better so there are low barriers to implementation. There’s not much more expense. Anyone can do this.”