While much progress has been made in preventing stroke in children with sickle cell disease (SCD), less is understood about silent cerebral infarct (SCI), a series of smaller neurologic events with no visible symptoms.

In patients with SCD, these events appear as early as infancy and accumulate with age, occurring in up to 37 percent of children with this diagnosis by age 14 and 53 percent of adults by age 30.

“It used to be that at least 10 percent of children with sickle cell would have a stroke by age 20. Now, when they receive all the appropriate preventive care, it’s 1 percent,” said Lori Jordan, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Pediatric Stroke Program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

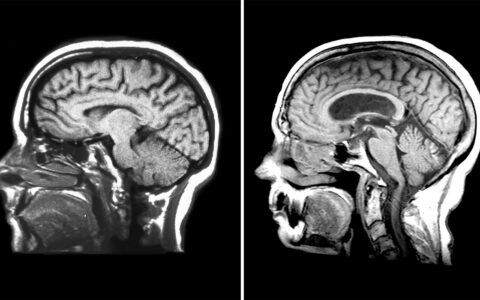

“What we haven’t been as successful at is preventing these silent infarcts. Patients don’t look like they’ve had a stroke, but on an MRI, we see small brain injuries that often are just a few millimeters in size.”

Jordan and colleagues previously demonstrated that 90 percent of infarcts in children with SCD occur in the deep white matter of the frontal and parietal lobes, within the cerebral blood flow border zone between the anterior cerebral and middle cerebral arteries.

Now, in a new study published in Neurology, the investigators demonstrate that tissue infarctions in adults with SCD stretch beyond the traditional border zones, with more than 45 percent of infarcts occurring in non-border zone regions.

Risk factors for SCI in both children and adults include low hemoglobin and elevated systolic blood pressure, but the mechanisms underlying their development are unclear.

“While adults may have similar regional ischemic involvement as children, we found that they may have additional vulnerability to silent infarcts, possibly due to the accumulation of more traditional stroke risk factors,” Jordan said.

Long-term Impact of SCIs

Jordan’s research focuses on brain health in children with SCD and other chronic medical conditions. “Silent infarcts in the brain impact the areas that control executive function and decision-making,” she explained.

In another recent study, Jordan and colleagues found that SCIs in children with SCD are associated with brain volume loss. Other studies have shown an average 5 IQ point decrement and poor academic performance following SCI.

“Plus, children with SCIs have a tenfold greater chance of having additional such infarcts over time, or even a more overt stroke,” Jordan said.

“Children who’ve had silent infarcts have a tenfold greater chance of having additional ones over time, or even a more overt stroke.”

Following her patients into young adulthood has sparked Jordan’s interest in how SCIs impact adults with SCD.

“If we can better understand what happens in the brains of adults, it helps us treat SCIs in kids more effectively,” she said.

In their new study, Jordan and colleagues looked at a large sample of adults ages 18-50 years from two centers to determine the distribution of SCIs in the brain. Using a 3D Brain MRI Arterial Territories Atlas, they conducted a more refined analysis of cerebral blood flow by brain region. Lesions that were at least 3 mm in size on MRI of the brain were defined as SCIs and plotted to create an infarct map for each participant.

“With advanced imaging tools, such as those developed by my neurology colleague Manus Donahue, Ph.D., we can get a better idea about the progression of infarct distribution and potential etiologies within specific arterial and border zones,” Jordan said.

Focus on Prevention

Most SCIs in children can be prevented by adhering to SCD treatment.

“However, some of these treatments have side effects and many parents don’t want to pursue the most aggressive treatment until absolutely necessary,” Jordan said.

She and Michael DeBaun, M.D., director of the Vanderbilt-Meharry Center for Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease, have been instrumental in developing the American Society for Hematology’s national guidelines for SCI testing.

“All children with sickle cell anemia – once they can hold still for MRI screening without anesthesia – need to get one,” Jordan said. “In our clinic, we do MRI at least once, and again with any symptoms. If we see a silent infarct, they typically get a scan every year. Every visit, we ask them questions that get at brain health, then we will do a scan if we or their parents think there are cognitive issues.”

“All children with sickle cell – once they can hold still for MRI screening without anesthesia – need to get one.”

Children with SCIs can receive regular blood transfusions to reduce the risk of a new stroke, another SCI, or both, she added. In addition, screening can identify children showing evidence of previous SCIs, making them eligible for school-based resources and other types of educational support.

“Our goal is to find ways to better support children with SCD in growing up to be healthy teenagers and successful, independent adults,” Jordan said.