In babies born with long-gap esophageal atresia (Type A EA), the esophagus has formed incompletely, leaving a space of 3 cm or more between the proximal and distal segments.

The customary treatment had been to replace the entire esophagus through autografting. In the early 2000s, a procedure called the Foker Process was developed that enabled surgeons to elongate and then attach the two esophageal sections.

In 2023, pediatric surgeon Jamie Robinson, M.D., Ph.D., of Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, led a surgical team in taking the procedure a step further using a minimally-invasive Foker process for surgery on a 9-month-old girl.

This technique has only been performed in a handful of centers across the nation and was the first to be done in Tennessee.

Robinson reports that the patient, now 18 months, is doing well and taking some food by mouth. To help manage reflux, Robinson performed a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, which improved a stricture that had developed.

“We are now starting to do consultations with physicians and parents in Tennessee and outlying states, offering guidance for the care of their patients with complex anomalies like this,” Robinson said. “Often, they will opt to transfer the patient into our care.”

Forms of EA

Esophageal atresia is rare, occurring in approximately 1 in 4,500 births worldwide. About 84 percent of EA patients have Type C EA, in which there is atresia with a distal tracheoesophageal fistula, but the ends of the esophagus are close enough to be sutured together. Other, rarer forms (Types B, D and E) involve one or more tracheal-esophageal fistulae and may or may not include long-gap EA.

Some EA anomalies are found in conjunction with Down syndrome (trisomy 21) and some are accompanied by one or more of a variety of abnormalities affecting the vertebrae, renal system, rectum, and/or limbs, with congenital heart disease foremost among them.

Complexities in Type A

Robinson’s patient had the second-most-common type of EA, Type A, affecting approximately 8 percent of children with the disease. These babies have historically required a full esophageal colonic or jejunal interposition or a gastric pull-up procedure, using part of the stomach to replace the esophagus.

This is a major operation, Robinson says, and particularly onerous, as it typically follows surgical repairs for congenital heart disease. It also carries a moderate risk of complications. Feeding through a gastric tube and oral and nasal suctioning is required between the surgeries.

“Over time, we’ve realized that those children can have a lot of long-term issues with feeding, reflux and strictures,” Robinson said. “And we saw that as they grew older, the repair didn’t work very well, rarely working like a normal esophagus. So we do everything that we can to save their native esophagus by getting the two ends together.”

Stitching for Traction

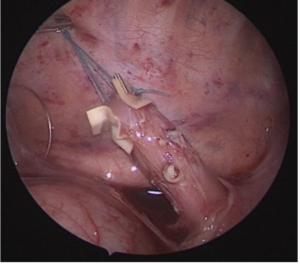

The Foker lengthening technique relies on stitching each of the atretic ends of esophagus and winding the suture upward or downward around rib bones to create tension on the esophagus.

“This can be done either through a thoracotomy or thoracoscopy,” Robinson said. “We insert a camera into the thoracic cavity and use small incisions to mobilize the upper and lower portions of the esophagus.”

Through anywhere from one to six follow-up procedures, surgeons tighten stitches to reestablish tension, gradually stretching the esophagus until the ends are ready to be sutured together.

“This vascularization and remodeling that takes place is an amazing regenerative phenomenon.”

“One of the beauties of this technique is that the esophageal walls are not thinned out but, rather, the esophageal tissue responds with robust angiogenesis, enabling normal thickness of the esophageal wall and lumen post-procedure,” Robinson said. “This vascularization and remodeling that takes place is an amazing regenerative phenomenon.”

The use of the native esophagus also maintains peristalsis, she notes, avoiding the higher risks of stasis, dysphagia, and gastric reflux seen in the gastric or colonic/jejunal replacement procedures.

Follow-up Care

In the new process, as in most that involve suturing, scar tissue can form at the repair site, creating a narrowing or stricture, sometimes worsened by underlying reflux, Robinson says.

“Dilation with a balloon is often needed as the esophagus heals, but we find that patients usually respond well to just a few dilations. Administering steroid injections into the scar tissue of the esophageal wall is another adjuvant option,” she said.

A Multispecialty Effort

Today, Monroe Carell is poised to become a leading center in complex esophageal and airway disease.

“Every week, I do some sort of esophageal surgery, whether it’s for primary or repeat EA repair or dilation,” she said. “We are also one of the first centers in the Southeast with expertise in posterior and anterior tracheopexies, so children with tracheomalacia – a commonly associated issue in babies with EA – can breathe freely without tracheal collapse.”

Robinson says she came to Monroe Carell seeking this opportunity to build and grow a complex aerodigestive and esophageal treatment center with an elite team of providers that includes otolaryngologists, gastroenterologists, nutritionists, social workers, and pulmonary specialists.

“Diseases like EA are very complex issues, involving breathing and swallowing, so it is so important to have a multidisciplinary view of the whole patient,” she said.