In critical care medicine, questions linger over the optimal level of oxygen to preserve brain function in mechanically ventilated patients.

The answers are expected to arrive soon, however, with a results of a study comparing the long-term impact of oxygen level adjustments on a range of cognitive domains.

“We don’t know which oxygen targets are best for mechanically ventilated patients, and different critical care societies have recommended different target levels. This uncertainty is like a lot of things we do in medicine, because there is no clear evidence.”

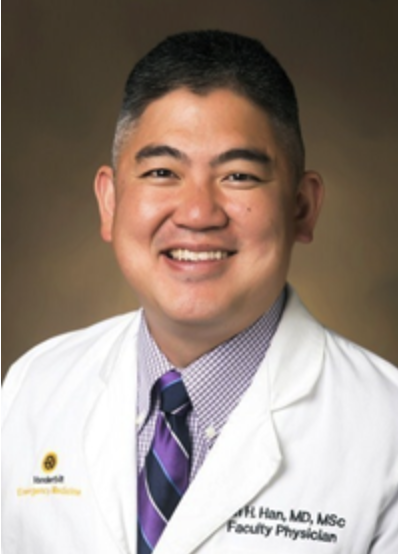

“We don’t know which oxygen targets are best for mechanically ventilated patients, and different critical care societies have recommended different target levels,” said Jin Ho Han, M.D., associate professor of emergency medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“This uncertainty is like a lot of things we do in medicine, because there is no clear evidence.”

Han and his colleagues will soon publish the results of a study designed to settle the matter, which they outlined in a BMJ Open article.

Damaged Brains, Damaged Lives

This uncertainty about oxygen level targets is a big problem, especially in critical care cases, Han said.

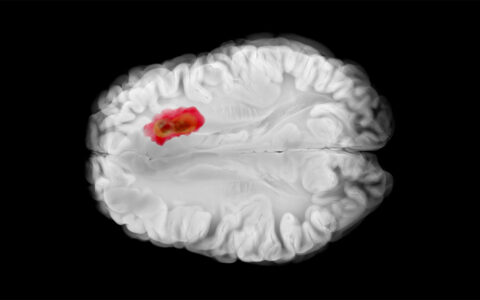

“One out of four patients who are critically ill develop a dementia-like illness,” Han said. “In people with acute respiratory distress syndrome, it can be up to 75 percent.”

These repercussions affect people of all ages.

“Patients who survive the critical illness often can’t go back to work or school or balance their checkbook. It’s incredible how debilitating critical illness can be for these patients,” the researcher added.

Across the Spectrum

Due to a lack of consensus on target oxygen levels, three approaches are currently in use:

- In the United States, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network regards oxygen levels acceptable as low as 88 percent.

- The British Thoracic Society, meanwhile, recommends pursuing levels as high as 98 percent.

- For the Thoracic society of Australia and New Zealand, recommendations fall between 92 and 96 percent oxygen.

“Some earlier studies have shown that low oxygen levels during critical illness are bad for brain function and can cause declines,” Han said. “Too high levels can damage the brain as well.”

As a scientist, Han said he is open to whatever the forthcoming study results demonstrate.

An Ancillary Study

The current study, Cognitive Outcomes in the Pragmatic Investigation of Optimal Oxygen Targets (CO-PILOT), is an outgrowth of a previous trial known as the Pragmatic Investigation of Optimal Oxygen Targets (PILOT).

PILOT was a randomized, controlled study that looked at the effects of low, medium, or high levels of oxygen on the number of calendar days the patient remained alive and ventilator-free, beginning the day after the final day of invasive ventilation through day 28.

“PILOT showed us that when critically ill adults were mechanically ventilated, the number of ventilator-free days didn’t differ for those who were randomized to the low, medium, or high oxygen targets,” Han said. “The CO-PILOT study was a natural outgrowth of that work, to let us look at cognitive outcomes.”

CO-PILOT uses a version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment designed to be administered over the phone to assess brain function. This tool includes questions that evaluate several cognitive domains, including attention, language, abstraction, delayed memory, and orientation.

Recruitment Challenges for CO-PILOT

CO-PILOT researchers contacted enrollees of the PILOT study 12 months after they were issued their breathing tube to ask if they wanted to join CO-PILOT and undergo cognitive assessments.

“We do a lot of things in medicine, especially in those who are critically ill, where we don’t truly understand how it affects long-term brain function.”

“About 3,000 patients had enrolled in the PILOT study; we had about 550 patients in CO-PILOT, and a lot of that drop off was because of death,” Han said. “There is a high mortality rate in this group of patients.”

Many of the patients who moved on from the ventilator are living with significant cognitive and physical disabilities, and people with significant impairments are less likely to participate in medical studies, he said.

Many are also dealing with psychological issues such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

“We do a lot of things in medicine, especially in those who are critically ill, where we don’t truly understand how it affects long-term brain function. We really need to do more studies of how what we do affects brain function and other outcomes,” Han said.