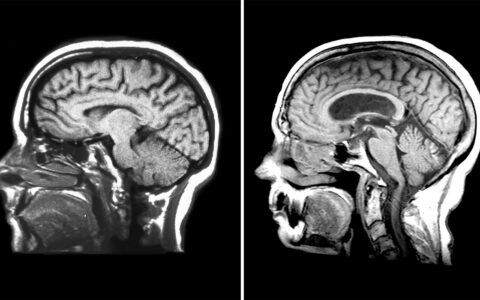

Children and youth with severe acute neurologic illnesses are at great risk for poor outcomes, including death, spurring a drive for better monitoring tools in the field of neurocritical care.

Toward that end, researchers at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt are investigating options that could allow more finely tuned observations and, potentially, more effective treatment. Some of the tools beginning to emerge are described by a team of Vanderbilt researchers in an article in Pediatric Neurology.

“The next phase of discovery for neurocritical care involves a shift away from us responding reactively to patients having setbacks,” said Michael Wolf, M.D., director of pediatric neurocritical care at Monroe Carell.

“Instead of waiting for a patient to have a crisis, with intracranial pressure building and the need for aggressive care, it would be wonderful to have tools to predict who was at greatest risk for dangerous events and to identify the time at which an intervention could be most meaningful in supporting good outcomes.”

The most promising new tools rely on advanced computation techniques, Wolf said.

“As we understand this at the biological and patient level, we can hope to gain insights to not just understand what is happening but how to improve treatment.”

Wolf particularly highlighted three innovative technologies: near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), advanced uses of the electroencephalogram (EEG), and the pressure reactivity index (PRx).

NIRS Goes Deep

“NIRS shines near-infrared light through the skin and skull to measure oxygenation of the surface of the brain,” Wolf said, comparing the procedure to a pulse oximetry reading. “From this information we can gain insight about blood flow to the brain.”

A key difference from pulse oximetry, though, is that NIRS devices can access oxygenation information from deep tissues, such as those in the brain, and can distinguish that data from the feedback from superficial tissues between the probe and tissues of interest.

Placement of an intracranial pressure monitor involves drilling a small hole in the skull and inserting a monitor, putting patients at risk of bleeding and infection, which can be “quite severe,” Wolf said.

“Researchers in the United States and around the world are attempting to find ways to use NIRS to predict a patients’ intracranial pressure, so one day we can use a combination of monitoring tools, perhaps including NIRS, to measure intracranial pressure without requiring an invasive procedure.”

Old Tool, New Interpretation

In neurocritical care, EEGs are typically used to detect seizure activity, so clinicians can intervene at once and prevent future seizures, Wolf explained.

“Now people are devising technologies that use advanced computations derived from EEG to build proactive, rather than reactive, strategies,” he said. “They are looking at EEG signatures that are not technically seizures but may represent increased risk of seizure, as well as looking at more subtle changes in the EEG.”

Expanding Options

The Pressure Reactivity Index, PRx, is a tool that monitors the brain’s ability to regulate its own blood flow by examining the relationship between arterial blood pressure and intracranial pressure.

Normally, cerebral blood flow remains steady despite changes in blood pressure, Wolf explained. If blood pressure rises, vessels in the brain narrow to keep blood flow normal. If blood pressure drops, vessels in the brain dilate, again keeping blood flow in the brain at normal levels. These adjustments in the brain affect intracranial pressure.

“In trauma, the ability of the blood vessels to dilate and constrict for the correct amount of blood flow can be impaired,” Wolf said.

Using PRx monitoring, the researchers have begun to understand that brains undergoing longer periods of impairment are more likely to have a poor outcome.

Wolf has also explored new approaches, including the use of ketamine, to treat high intracranial pressures in children after traumatic brain injury.

Being There for Families

These technologies have the potential to alert clinicians about when to intervene, Wolf indicated.

“Parents and kids come to us at the worst time of their life,” he said. “Parents are so worried, with so many questions: Will my child survive? What will my child’s life look like? What can we do now to give them the best chance for a long, fruitful life?”

Such moments and questions are what Wolf says motivate him and his colleagues to keep working to improve care for children with critical brain injuries.