Nomograms are commonly used in oncology for risk assessment and to predict a patient’s surgical outcomes and survival.

However, colorectal cancer surgeons have lacked such a tool. Instead, they have relied on their own risk calculations after considering MRI images and clinical characteristics to predict key outcomes. Chief among their concerns is whether circumferential resection margins (CRM) – an important prognostic factor in local recurrence – will be positive or negative.

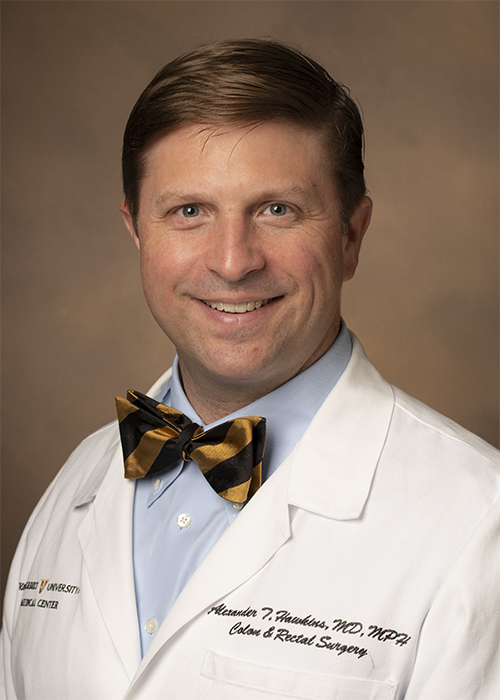

Since treatment decisions can differ based on this information, use of a formal risk calculator stands to improve outcomes. This led colorectal surgeons Alexander Hawkins, M.D., director of the Colorectal Research Center, and Molly Ford, M.D., an associate professor of surgery and director of the Vanderbilt Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, to approach Vanderbilt resident Megan Shroder, M.D., with a proposal: to investigate the key predictive factors for determining positive CRM probabilities and their relative weight. The result was the first nomogram and web-based calculator for predicting positive or negative CRM.

“There have been many studies that look at patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment regimens and operative approach to help identify what factors independently put a patient at higher risk,” Shroder said. “But this is the first time we’ve had a clinical tool that puts all this together and gives you a quantified predictive value.”

Margin Predictions Drive Therapy

The gold standard tool for predicting positive CRM risk in rectal cancer is MRI imaging.

“MRI does an excellent job of predicting circumferential margins anatomically, but we know other factors also impact the patient’s risk,” Shroder said.

With a positive CRM, the risk of local recurrence has been found to be around 17 percent, compared with 3.4 percent for patients with a negative CRM. These numbers factor in the use of other therapies, such as radiation and chemotherapy. The five-year overall survival rate is significantly higher for those with a negative CRM, Shroder added.

“Local recurrence is often very difficult to deal with because you have had surgery and possibly radiation in that location. It can be quite painful and difficult to manage and can also be deadly for the patient,” Shroder said.

There are modifications a surgeon can make if made aware that the patient is at high risk for a positive CRM. Now, this new tool can help guide the plan.

“This tool can tell you that you may need to do a bit more extensive resection, or that you should perhaps wait a little longer to let the chemotherapy and radiation take effect,” Hawkins said. “If you don’t think you’re going to be able to get clear margins, or you think there’s a very high likelihood that they’ll come out with positive margins, then the surgery may actually set them back by delaying other therapies.”

Predictive Value of the Nomogram

Shroder and fellow researchers presented data that helps validate their nomogram at a meeting of the Tennessee Chapter of the American College of Surgeons.

“This is the first time we’ve had a clinical tool that puts all this together and gives you a quantified predictive value.”

The researchers looked at the National Cancer Database records on 29,118 patients who had total mesorectal excision for clinical stage I-III rectal cancer, extracting data on many characteristics, from tumor size to operative approach. Patients who had had an emergency or palliative operation, transanal resection, resection for recurrence, or stage IV cancer were excluded.

The records showed that 8.6 percent of the patients had a positive CRM.

The team worked with Vanderbilt biostatisticians to evaluate the relationship between patient and tumor characteristics with a positive margin outcome. These were folded into an algorithm with a moderate to high predictive value.

From Judgment Call to More Informed Decisions

Shroder says some of the key points considered when making surgical decisions are tumor size and aggressiveness, whether the patient has had surgery in that area before and may have scarring, level of illness at baseline, and ability to tolerate a long surgery.

“Most of these factors don’t show up on an MRI, but now the surgeon can combine a weighted compilation of these factors with the MRI to make treatment decisions,” Shroder said.

She said intricate conversation should take place between each patient, surgeon, oncology team members and others according to the details of the case.

“The more we can add to that conversation that is meaningful and also simplifying, the better,” she said.