For the past decade, the options in treatment for epilepsy surgery have been resection through craniotomy, brain stimulation implants and laser ablation. Yet there is an evolution underway. Improved outcomes are being observed in both resection and minimally invasive procedures, and a parallel expansion of the candidate pool for each.

“About half of our patients still undergo some kind of surgical resection, and the other half have a less invasive surgery, such as laser ablation or neurostimulator implantation. But the whole pie is expanding as we improve our hypotheses and success rates in these categories,” said Dario Englot, M.D., director of functional neurosurgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“I don’t think it will be long before we start independently using VBM data to go straight to definitive treatment.”

“Particularly with poorly localized seizures, we can now use improved stereotactic electroencephalograms (SEEGs) to obtain recordings from multiple regions bilaterally, allowing many people who would have once had few treatment options to become surgical candidates,” Englot said.

More Palatable, Precise Epilepsy Surgery Treatments

Not only are more patients eligible for epilepsy surgery, but Englot says technologies such as deep brain stimulation make treatment more palatable to many who would not otherwise move forward with surgery. “Patients with seizures that are localized to a critical area for memory, language or motor function — areas that can’t be removed – are now in the candidate pool.”

Further, certain patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) are newly eligible for responsive neurostimulation (RNS) implants under FDA breakthrough status. “To finally have surgical options for patients with generalized epilepsy is a big step since these patients are extremely debilitated and difficult to treat,” Englot said.

“Particularly with poorly localized seizures, we can now use improved stereotactic electroencephalograms (SEEGs) to obtain recordings from multiple regions bilaterally.”

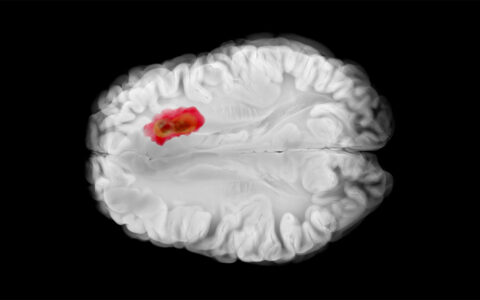

Laser ablation therapy is one of the therapies that is becoming more precise and less invasive, appealing to patients who have well-circumscribed foci in the hippocampus, the most common site of focal seizures in adults. “The efficacy is lower than with resection, but it is still high, and the patient spends much less time in the hospital and off work,” said Angela Crudele, M.D., epileptologist and assistant professor of neurology at Vanderbilt.

Resection, however, remains the gold standard in temporal lobe epilepsy treatment. Englot and his team are demonstrating high success with selective amygdalohippocampectomies. A recent paper describes their outcomes after 211 of these procedures at Vanderbilt, reporting favorable surgical outcomes and low morbidity.

Sharpening the Spear

Finding seizure foci remains the crucial and often daunting challenge. To home in on these, Vanderbilt researchers have improved SEEG-guided electrode placement for both presurgical planning and implantation of stimulation devices. “With robot guidance and 3D-printed frames, today we can place electrodes more precisely for recording brain activity and avoid dangerous areas, including blood vessels,” Englot said.

Victoria Morgan, Ph.D., a professor of radiology and radiological sciences and biomedical engineering, is working to demystify seizure origins. Through voxel-based morphometry (VBM), her work aims at localizing seizures by identifying focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) at the gray/white matter border, where they are likely to arise.

“VBM can help us target our SEEG electrodes,” Crudele said. “I don’t think it will be long before we start independently using VBM data to go straight to definitive treatment.”

A Two-minute SEEG

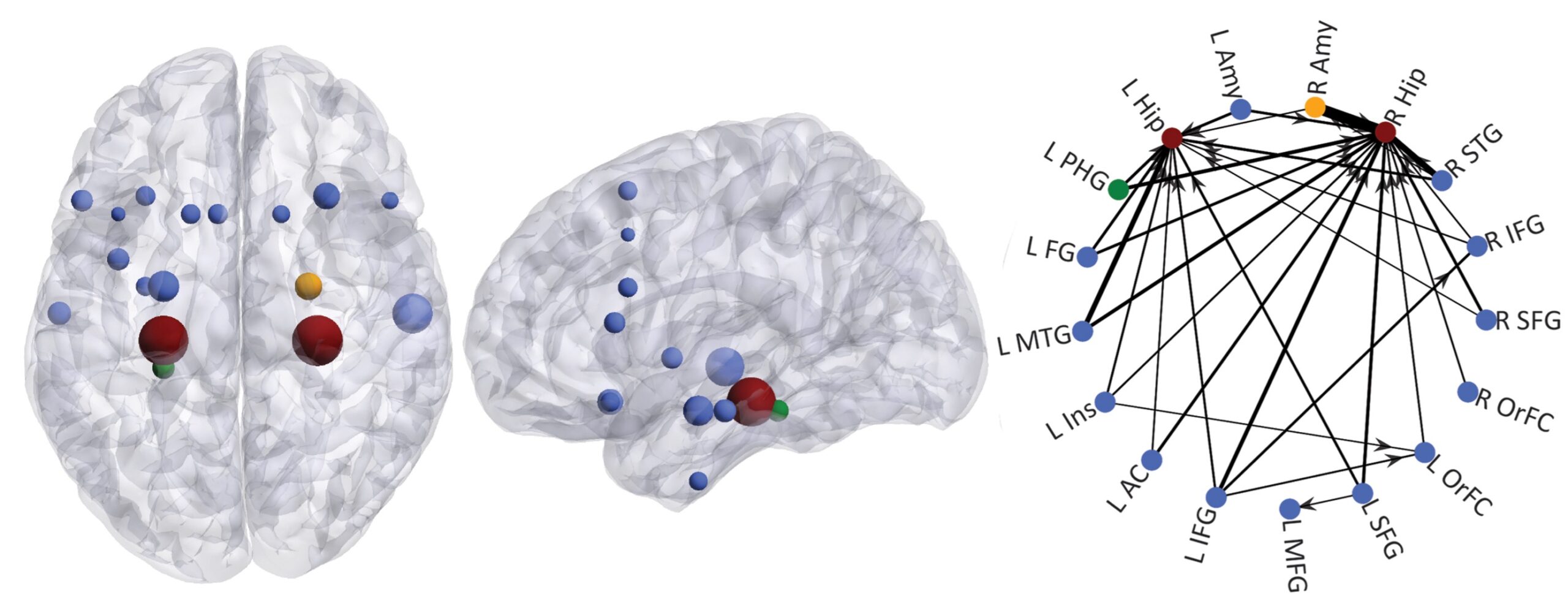

To lower the burden of the diagnostic process, Englot is currently testing a “resting state” predictive functional connectivity model that could equal or surpass the utility of standard SEEG studies. Instead of provoking seizures over a long hospital stay, the patient’s neural network is analyzed by fMRI, based on a two-minute “resting state” SEEG, to predict seizure foci. His team recently demonstrated an area under the receiver operator curve of 0/88 and an accuracy of 84.3 percent.

The advance offers hope where there is often little to be found. Crudele works with patients with infrequent seizures who invest weeks or months in a hospital and can end up with only three to five seizures over that period. “With resting state SEEG, you are using passive data collection that isn’t dependent on an active seizure to localize the epilepsy and drawing inferences from the directionality of the connections.”

Englot says the capability to build more generalizable maps of seizure activity may be the source of the greatest advances in quelling seizures for more patients, in a shorter time frame, and with less discomfort. “Our procedures are becoming less invasive and more expansive the more we learn about brain connectivity,” he said.