Current treatments for endometriosis include surgical excision or hormone therapy, both of which have variable success and carry significant downsides. The limited toolkit is due in part to a lack of basic research into the condition, says Lara Harvey, M.D., an obstetrician and gynecologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“It’s a relatively underfunded and under-investigated problem, given the broad impact and quality of life issues that it causes,” Harvey said. “It’s frustrating from a patient perspective to have such a limited repertoire of medications and therapies.”

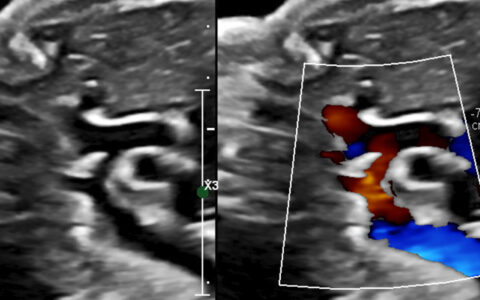

In a new study, Harvey and Kate Chaves, M.D., a fellow in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, are investigating a previously unexplored factor that could drive the development of endometriosis – the immune response to tissue accumulation in the peritoneum. “If we learn that there is an immunologic component to endometriosis, that brings in a whole new pathway for potential treatments,” Harvey said.

“If we learn that there is an immunologic component to endometriosis, that brings in a whole new pathway for potential treatments.”

A Novel Laboratory Model

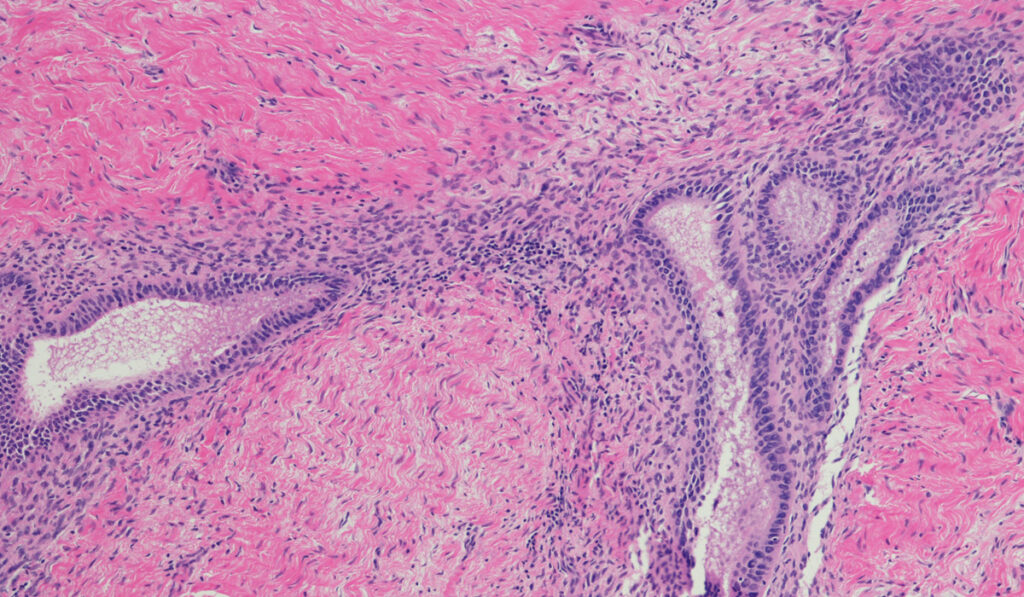

This study is part of a larger effort at Vanderbilt to elucidate the etiology of endometriosis using a novel “organ-on-a-chip” model developed by Kevin Osteen, Ph.D., Pierre Soupart Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Vanderbilt. Osteen and colleague Kaylon Bruner-Tran, Ph.D., are using the model to identify environmental chemicals that may influence physiologic processes in ectopic tissues. They have also established several endometriosis mouse models to validate the work.

In the new study, the team of investigators will focus on unraveling immune responses in endometriosis. Bruner-Tran and Osteen have already established that injecting healthy immune cells into mice is protective against endometriosis. The investigators now hypothesize that women with endometriosis could have suboptimal or conflicting immune responses and an inability to clear ectopic cells.

“One thing we want to learn is whether this anomalous immune response is a prerequisite for, or a response to, endometriosis,” she said.

Teasing Apart the Immune Responses

Using Bruner-Tran and Osteen’s mouse models, the team will explore how tissue or immune cells from women with endometriosis impact the peritoneal inflammatory environment and associated lesions.

“We will be exposing mice to endometriosis tissue and non-endometriosis tissue, and also to the immune milieu from women with and without endometriosis,” Harvey said. “This will reveal the relative contributions from just the endometriosis tissue, as well as from the immune profile.”

The team also seeks to learn whether particular characteristics of immune cells trigger endometriosis or whether it is more broadly a function of an overactive immune response. They hypothesize that the culprit is the particular immune cell phenotype, and that this phenotype is associated with a high concentration of specific growth factors and cytokines.

Narrowing in on Treatments

All of the tissue samples for the new study are donated by women undergoing surgical excision, currently the gold standard treatment for endometriosis. With such few treatment options available to patients, Harvey is hopeful that the new study may reveal ways to target the immune system.

“Alternative medical therapies are sorely needed,” Harvey said. “Even though a novel drug might be a long way off, just adding to our understanding of how the disease develops and finding another pathway to focus on for drug development brings some more hope for the disease.”