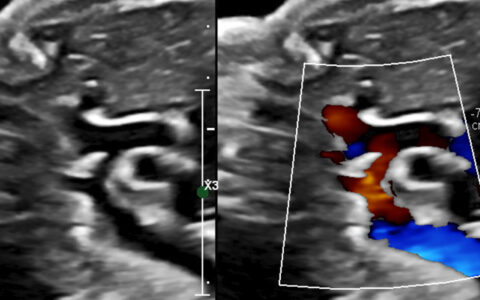

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has made news during COVID-19 as a life-saving modality for adult patients with severe disease. ECMO has long been a staple for children with congenital disorders, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and often as a bridge to heart transplant.

For the fifth straight time in 15 years, the pediatric ECMO program at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt has achieved gold level status from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO), which sets standards and provides support for ECMO programs internationally. The ELSO Gold Level Award of Excellence recognizes ECMO centers that provide exceptional outcomes, innovation, satisfaction and quality.

“Maintaining the requirements for the ELSO Award of Excellence requires innovation and vigilance – always being prepared for the unexpected,” said ECMO program manager Daphne Hardison, M.S.N. Hardison credits the success of Vanderbilt’s program in part to its emphasis on rigorous ECMO training. “Our program includes a team of advanced critical care ECMO specialists who are committed to quality of care.”

Building ECMO Expertise

Children’s Hospital started its ECMO program in 1989. Today, the program treats an average of 55 children a year. “Over the past thirty years, we have developed a very ECMO-specialist-centric program,” said Brian Bridges, M.D., the program’s medical director. “We are proud that amongst a very critical cohort of patients and a lot of great ECMO centers, our patient discharge rate is 10 percent above the average.”

“We are proud that amongst a very critical cohort of patients and a lot of great ECMO centers, our patient discharge rate is 10 percent above the average.”

Surgeon Robert Bartlett, M.D., first introduced ECMO in adults in the 1970s, but early use was confounded by aggressive mechanical ventilation. Bridges says ECMO was far more effective in children from the start. “Since ECMO support for pediatric patients was concentrated in a few centers, those centers readily gained experience and improved outcomes with these most critically ill patients,” he said.

Focus on Specialists

Bridges says at Children’s Hospital, the most elite ICU nurses and respiratory therapists (RTs) are selected to train in ECMO delivery. “These nurses and RTs may continue in their broader roles, but their primary specialty and priority will be ECMO, spending their entire shift with the patient.”

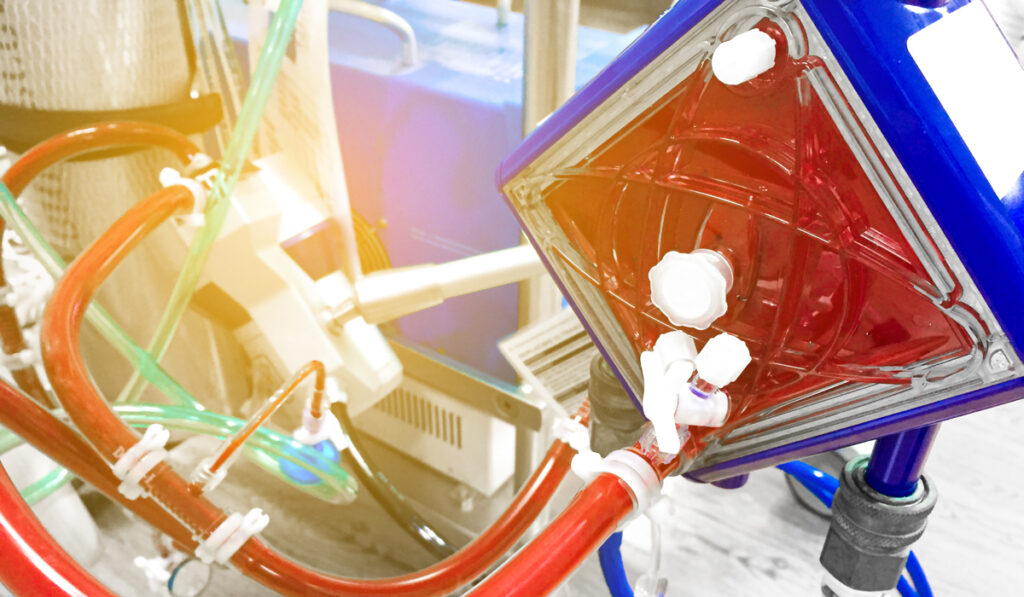

ECMO providers spend hundreds of hours in one-on-one training at the pump, going through simulations of what can go wrong. Chief among these are circuit clotting, air getting into the pump, blood coming from the pump, and myriad physiological problems the patient may develop.

“A lot of programs choose not to have ECMO specialists with the pump all the time,” Bridges said. “But we have made a conscious decision not to back off of that continuous, in-person monitoring.”

“ECMO is a lot like anesthesiology. There can be hours of boredom punctuated by minutes of terror once something goes wrong. We are always preparing for the rare moments when an unexpected emergency arises,” he added.

“We have made a conscious decision not to back off of that continuous, in-person monitoring.”

Improving the ECMO Mechanics

Improvements in anticoagulation drugs, ECMO circuitry and oxygenators have advanced therapy in recent years. The Children’s Hospital team contributed to this evolution through their research on anticoagulant protocols, which informed best practices in the fifth edition of the ELSO Red Book.

“Walking the line between hemorrhage risk and circuit clotting is one of the most challenging aspects of ECMO, and I think that is something we manage particularly well here,” Bridges said.

Flexibility to adjust the ECMO system is key to meeting complex patient needs and caring for the smallest patients. The team at Children’s Hospital has the capability to switch between ECMO configurations, incorporate other extracorporeal life support like dialysis devices into ECMO, or perform therapeutic plasma exchange when the patient has multiple organ failure and low platelets.

“The technology is markedly better than decades or even 10 years ago,” Bridges said. “As we look ahead to the specter of combined influenza and COVID-19 this winter, I’m pleased to say that we are ready for whatever comes our way.”