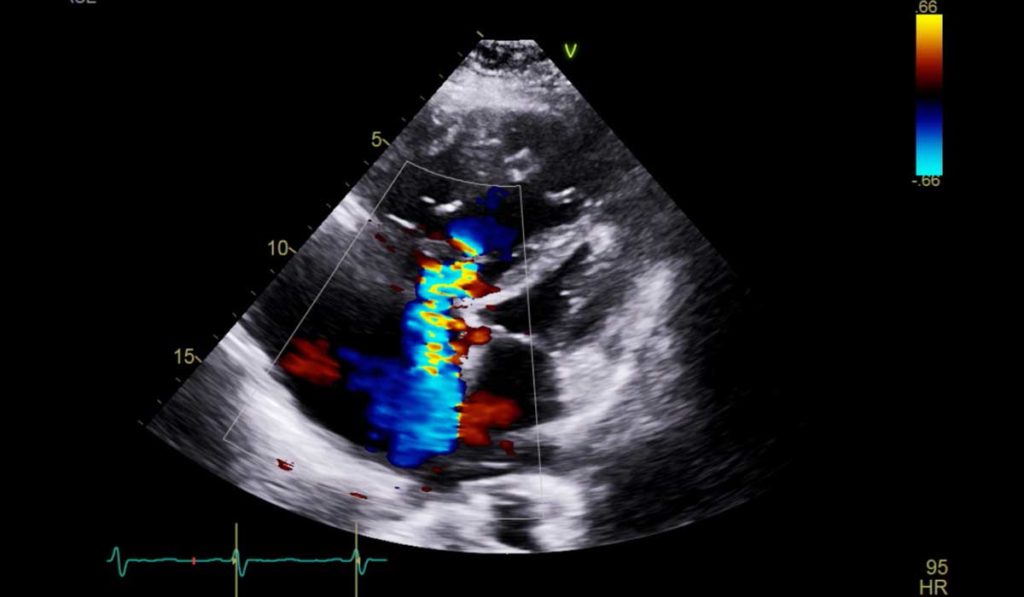

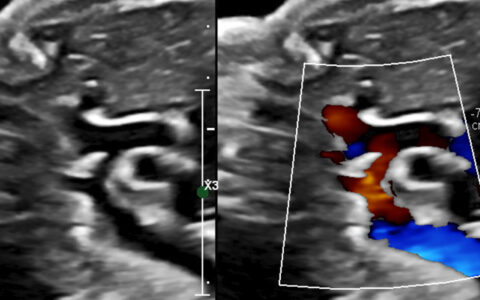

The American College of Cardiology, European Society of Cardiology and American Heart Association describe mild pulmonary hypertension (PH) as a right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) between 33 and 39 mmHg, as measured through echocardiographic exam (21-25 mmHg equivalent in catheterization). Guidelines only recommend invasive hemodynamic evaluation above an RVSP of 40 mmHg or 2.8 m/s tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV), in the presence of dypsnea or right ventricular dysfunction.

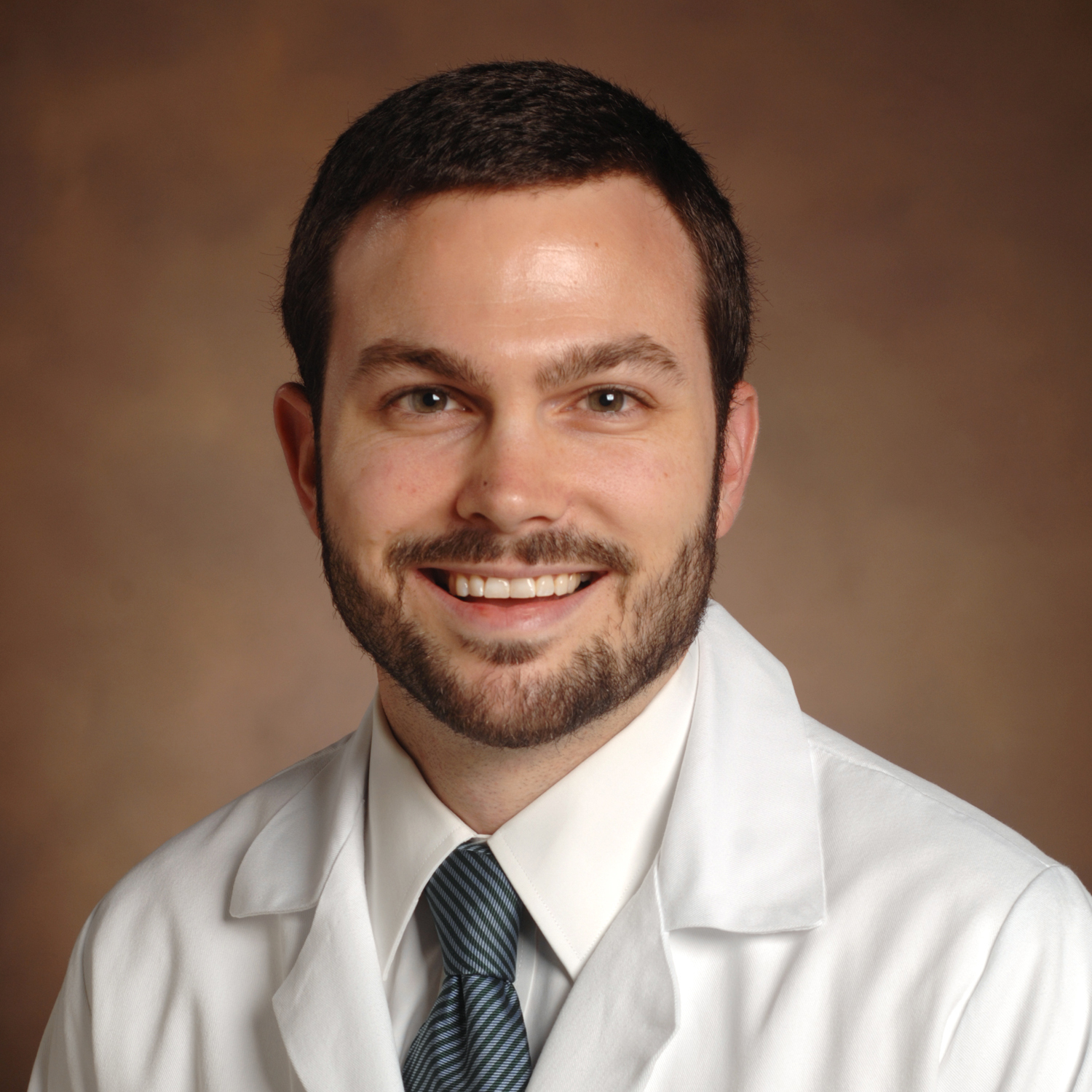

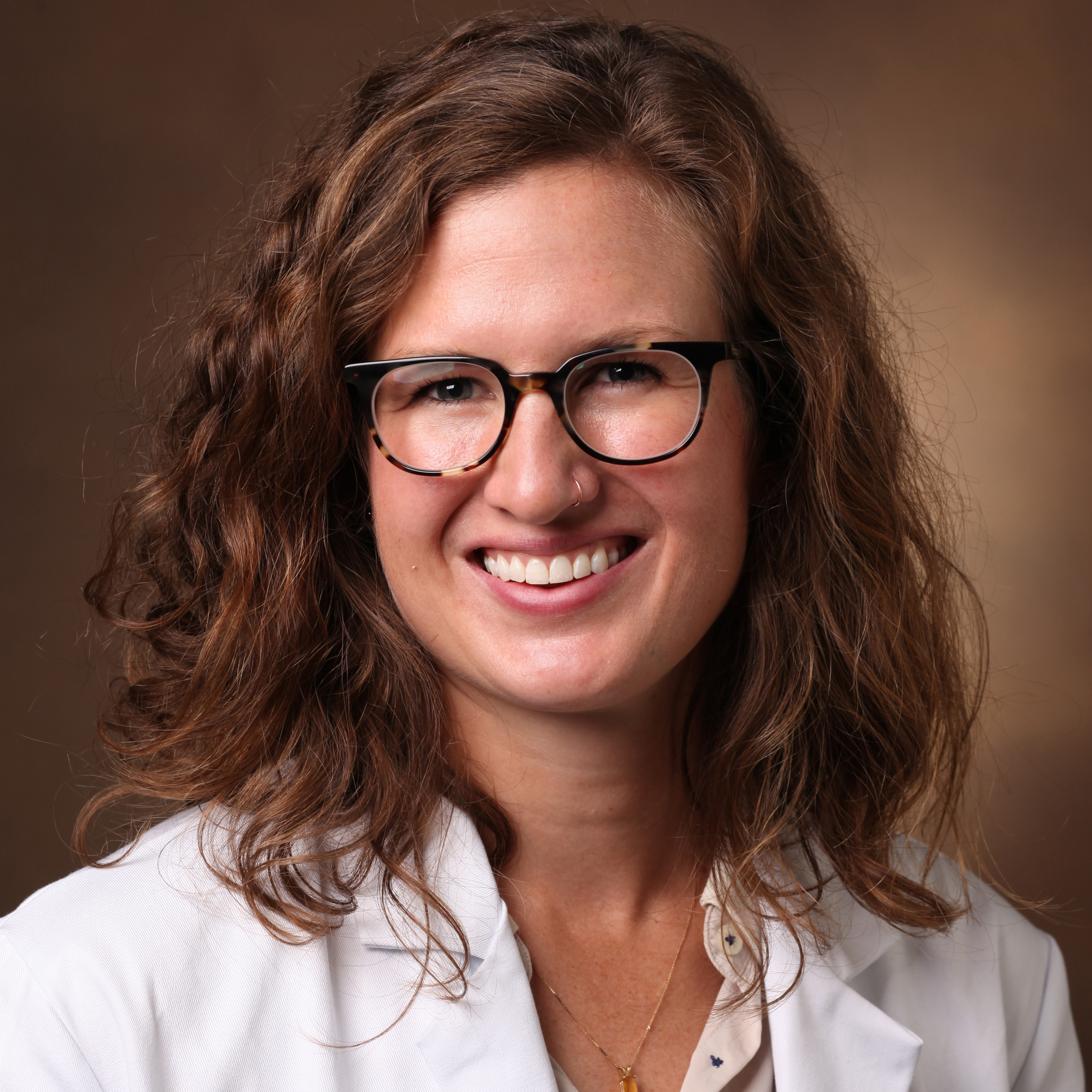

New evidence suggests that this threshold for evaluation may be too high to effectively screen in patients who face significant cardiovascular disease risks. Evan Brittain, M.D., director of the cardiovascular imaging fellowship at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is the primary investigator on a new study in JAMA Cardiology demonstrating a strong association between mildly elevated RVSP and poor outcomes. The study may encourage guideline changes toward earlier catheter evaluations in borderline situations.

“What we found is that ‘normal’ isn’t normal,” Brittain said. “Patients with pressure values in this range are not currently being identified as being at risk for adverse outcomes,” Brittain says their research supports increased surveillance and investigation of these patients for comorbidities like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure.

Scope of the Study

The researchers explored the data on 47,784 patients over 17 years who were referred for echocardiographic exams and had recorded RVSP or tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV) values. The records also contained data on atrial size, right atrial pressure, and right ventricle size, with 1,994 of them including tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion as a measure of right ventricular function.

Brittain and colleagues specifically analyzed RVSP (4 TRV2 + right atrial pressure), an echo-derived estimate of pulmonary pressure, as a continuous variable to determine at what pressure clinical risk emerges.

Higher Pulmonary Pressures, Higher Risk

In the 3,492 deaths that occurred, the adjusted risk of all-cause mortality was 50 percent higher in patients with mild echocardiographic PH versus the reference group of patients with RVSP less than 33 mmHg. Increased risk began at 27 mmHg, well within the “normal range” for RVSP measurements and doubled over the reference group at 35 mmHg, and at a TRV value of 2.8m/sec.

In subgroup analyses, they found a significant increase in mortality among patients with heart failure or COPD if they had mildly elevated versus normal RVSP. RV dilation and other objective and subjective measures were all worse in patients with RSVP of 33 to 39 mmHg versus “normal” of less than 33 mmHg.

“This study adds to the current literature by examining quantitative RV function and right ventricle-pulmonary artery coupling, including additional adjustments for established PH risk factors in a racially diverse referral population,” said Jessica Huston, M.D., lead author on the study.

The Forgotten Ventricle

“The main objective is to flag that these pressures are not normal, so people are thoughtfully assessing what to do next.”

The authors suggest that mild elevations should prompt clinicians to seek and treat underlying comorbidities, such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, obstructive sleep apnea, or COPD. “The main objective is to flag that these pressures are not normal, so people are thoughtfully assessing what to do next,” Huston said.

“We are trying to fill a gap in the research to date, understand the impact modestly elevated RVSP has on RV dysfunction, alone or in conjunction with comorbidities,” Huston added. “One problem with this is that our measures for how well the RV functions are quite insensitive compared with the ones we use to assess the left ventricle. The right ventricle is the final common pathway, and while resilient, once it slides into failure, prognosis is poor.”