A 26-year-old man with no prior medical symptoms was having trouble walking. He had pain and weakness throughout his body that was getting worse. He’d been diagnosed with a degenerative disk, a hip fracture and psoriatic arthritis, but none of the recommended therapies were working.

“He was a young, otherwise healthy man who had become progressively and rapidly disabled. His degree of disability was profound for somebody of his age,” said Kathryn Dahir, M.D., an endocrinologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

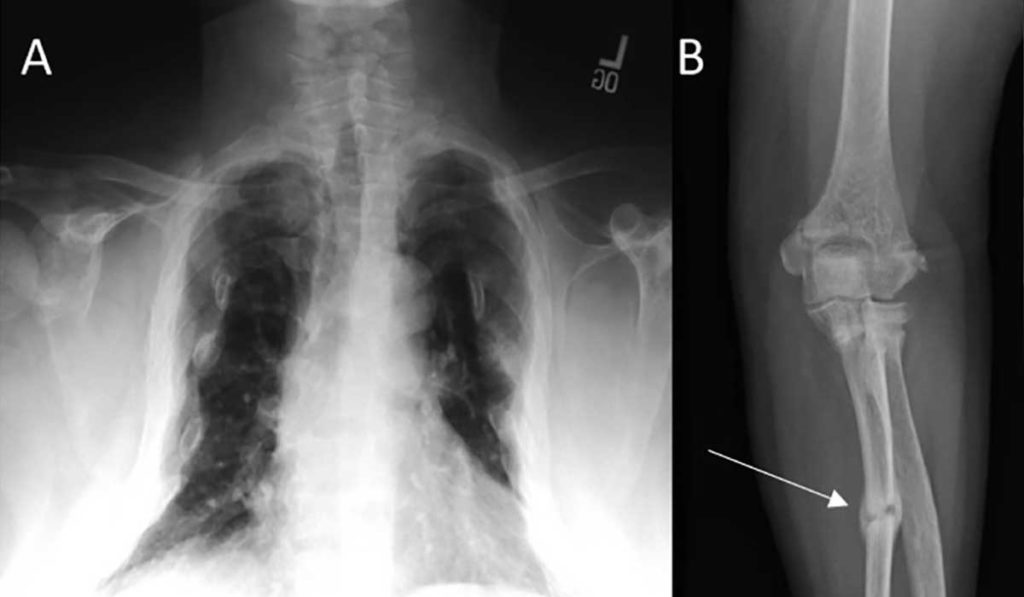

By the time Dahir saw the patient, he had fallen so many times that he had fractures in his ribs, ankles and femur. He couldn’t walk unassisted or get up on the exam table by himself. Dahir, a recognized expert in bone disease, immediately began diagnostics with one condition in mind: osteomalacia.

A Silent Phosphorous Leech

The severe symptoms led Dahir to check the patient’s bone metabolism. Dahir applied her expertise and requested levels not typically included in a comprehensive metabolic profile. Blood tests revealed relatively low phosphorous levels and high fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) levels.

In bone, FGF23 helps regulate the balance of phosphorous, calcium and magnesium. It prevents phosphorous levels from getting too high by increasing its excretion from bone. It’s a critical hormone – mutations in FGF23 can lead to severe bone diseases such as Rickets.

The blood tests suggested something was pumping out FGF23 to leech phosphorous from the patient’s bones, weakening them, and causing osteomalacia symptoms. Dahir believed a tumor could be the culprit.

Clues from a PET Scan

Tumor-induced osteomalacia is so rare that published case reports number only in the teens. But Dahir believed a tiny tumor, perhaps in the hands, feet or nasal cavity like she’d read about in the reports, might be drawing phosphorous out of the patient’s bones.

A PET scan indeed showed a small tumor – but it was directly under the temporal lobe.

Said Dahir, “It was a really rare disease in and of itself, coupled with the rarest place you can find a tumor like this.” The tumor’s location made it seem more like a meningioma, which is benign, and not a cause for invasive brain surgery.

“It was a really rare disease in and of itself, coupled with the rarest place you can find a tumor like this.”

Dahir sent the PET scan to a team of neurosurgeons at Vanderbilt. Given their extensive experience with meningiomas, their initial reaction was to avoid high-risk surgery to remove the tumor, and instead use MRIs to monitor it. But after more research, including 11 case reports provided by the patient’s wife, the possibility for a cure was too tempting. If indeed the tumor was making FGF23, removing it could completely reverse the symptoms.

Rapid Recovery

Reid Thompson, M.D., director of neurosurgical oncology at Vanderbilt, agreed to operate after learning more about tumor-induced osteomalacia. Thompson removed the tumor and the patient’s FGF23 levels began dropping immediately. Within a few weeks, the patient was climbing stairs. Now, his bone density has returned to normal.

Said Dahir, “In six months, [he] went from walker, to cane, to nothing, to square dancing. He is healing his osteomalacia and has corrected all of his metabolic abnormalities due to low phosphorous levels. It has been so rewarding to see someone get better so quickly.”

Dahir noted that many cases of tumor-induced osteomalacia go undiagnosed for years. Her patient’s own advocacy played a significant role in making the diagnosis rise to the top of the differential. “I think we all got lucky because [the patient and his wife] both pressed for a diagnosis and did their research,” Dahir said. “It doesn’t get more patient-centered than that.”