Epidemiologic evidence indicates that men with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have a faster decline in renal function compared to women. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. There have been few formal studies of sex differences in experimental kidney disease, and an over-reliance on male animal models.

A new study published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology reports that sex differences in renal epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression levels play a role in susceptibility to progressive kidney injury, and that these differences may be mediated in part by testosterone.

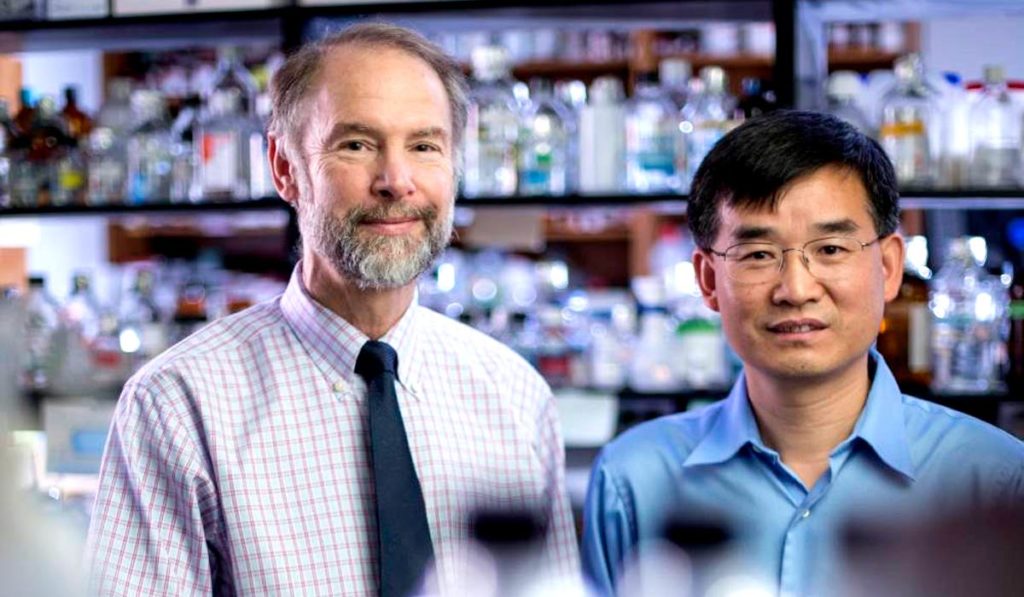

“It was a little bit of a serendipitous finding,” said Raymond Harris, M.D., the Ann and Roscoe R. Robinson Chair in Nephrology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and lead author on the study. Ming-Zhi Zhang, M.D., associate professor of medicine, is first author on the study.

EGFR Activity in Kidney Injury

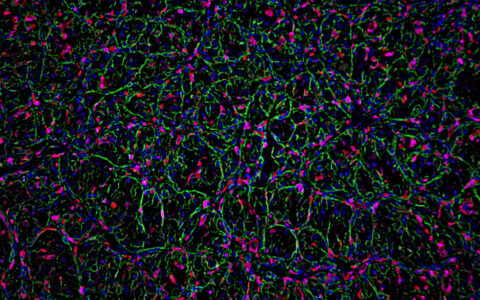

Harris and Zhang use models of kidney injury to ask questions about what causes the kidney to develop progressive fibrosis, which is the ultimate mechanism for the kidney to fail.

“One of our longtime interests has been the EGF receptor axis,” Harris said. “EGF is made in the kidney in high concentrations. Once we were able to utilize genetically modified animals as well as specific inhibitors of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity, we found that inhibiting EGFR could slow the development and reduce the amount of fibrosis.”

“We found that inhibiting EGFR could slow the development and reduce the amount of fibrosis.”

A Role for Testosterone

The serendipitous discovery about the role of EGFR expression and sex differences in kidney injury came when Zhang started doing experiments in Dsk5 mice, which have a gain-of-function allele that makes EGFR constitutively activated.

“I didn’t think this new mouse model was going to tell us anything new, and it turned out to be quite interesting,” Harris said. “The male mice developed really profound, spontaneous kidney injury after a couple of months of age. When we looked at the female mice at the same age, we found they had almost no injury.”

“The male mice developed really profound, spontaneous kidney injury after a couple of months of age. When we looked at the female mice at the same age, we found they had almost no injury.”

Harris and Zhang found that in wildtype mice, renal EGFR expression levels were comparable in female and male mice at postnatal day seven, but that in age-matched adult mice, females had significantly lower renal EGFR expression compared to males. Similar sex differences in renal EGFR expression were observed in adult human kidneys.

Their initial thought was that the differences in renal EGFR expression levels might be due to increased sex hormones in females. However, they found that oophorectomy had no effect on renal EGFR levels in female Dsk5 mice. Instead, castration protected male Dsk5 mice from kidney injury and caused a reduction in renal EGFR expression levels. In female Dsk5 mice, testosterone increased both renal injury and EGFR expression levels.

Future Therapies

Despite being used as successful chemotherapeutics, EGFR inhibitors are not a practical treatment option for progressive kidney injury due to severe cutaneous side-effects. Harris explains that it may be possible to avoid these side effects by using EGFR inhibitors at lower doses than those used to treat cancer, and there is an ongoing clinical trial for Polycystic Kidney Disease using EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Currently, Harris and Zhang are exploring the idea of inhibiting EGFR activity indirectly, by disrupting processes upstream or downstream of the receptor.

“There are a lot of possibilities for further therapies,” Harris said. He is particularly excited about the success of the ongoing partnership between Vanderbilt and Bayer geared at finding new drug therapies for kidney disease. “There are some promising novel therapies that may come to early clinical trials.”