Recurrent diverticulitis causes significant personal hardship for many sufferers, but in most cases is not a fatal disease. Because treatment options are not generally life or death decisions, there has been little rigorous research to date on long-term outcomes with surgical intervention versus observation for patients with recurrent episodes.

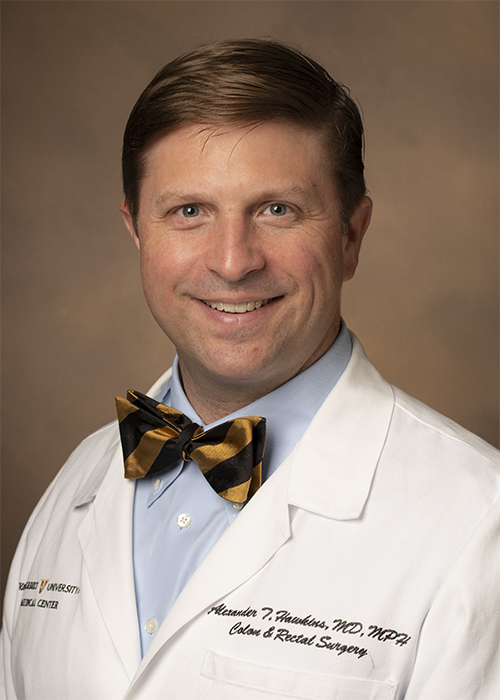

Assisted by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Alexander Hawkins, M.D., colorectal surgeon at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is researching which patients benefit from surgery versus observation, based on long-term impact on quality of life and economic factors.

“Patients may be more concerned about how their bowel function is, how they are going to feel a year out, freedom from anxiety over recurrences.”

“We have data on short-term outcomes like mortality, complication rates, hospital length of stay and readmissions, but patients may be more concerned about how their bowel function is, how they are going to feel a year out, freedom from anxiety over recurrences,” Hawkins said.

Elective surgery decisions are frequently made by patients and their doctors based on unstructured conversations, Hawkins said, with limited knowledge about how patients fare once they leave the hospital or if they instead choose observation. While official guidelines prioritize individualized decisions, Hawkins says that a lot of times, the old “three strikes and you’re out” rule still prevails: surgery is an automatic decision upon a patient’s third acute episode.

Filling the Knowledge Gap

Hawkins plans to recruit patients for a longitudinal, multicenter study that will extend into 2022. It includes a retrospective analysis of electronic health records of patients who have undergone either observation or sigmoid colectomy. It also includes a prospective study of 120 patients at a significant decision point between surgery or observation.

Hawkins plans to assess patient outcomes at baseline, three, six and twelve months, along with health economic variables, which include a heavy emphasis on quality of life changes and patients’ reflections on the decision.

“We are using patient reporting outcome measures to get at how patients view their quality of life along specific parameters, and overall,” Hawkins said. “How has the decision impacted their ability to work—have they experienced another episode, have they had to miss work, miss family vacations?”

“There are many, many patients in a gray area.”

In Hawkins’ experience, most surgical patients are glad they had the surgery, but clarity around who will and won’t is missing. The study could reveal important information as to how patients perceive the success or failure of their treatment choice. “Patients with poor quality of life generally do well with surgery and those with an acceptable or good quality of life do well with observation. That stands to reason. But we don’t have any real data to support that assumption, and there are many, many patients in a gray area,” he said.

Finding Equipoise

Today, the efficacy of non-surgical management of the disease is highly variable, Hawkins said. “We can ask patients to stop smoking, to lose weight, to increase fiber in their diet, but whether they do or not, we are very poor at predicting who is going to have recurrent episodes.”

While the data Hawkins collects may help with these predictions, his primary goal is to help inform more personalized decisions. “We will be able to sit down with patients and say that others with your baseline quality of life scores and your medical and demographic profile did well with surgery or with observation.”

“This data will help surgeons get away from relying on a gestalt feeling,” Hawkins said. “The goal of this research is to resolve the equipoise that is missing from our decision-making today.”