With 36 years of experience, Lynne Stevenson, M.D., of Vanderbilt University Medical Center has seen how new technologies have transformed cardiomyopathy patient outcomes. New devices, promising trials and laboratory research have ushered in a clearer understanding of heart “failure”—and may be making the term obsolete, says Stevenson. Discover interviewed Stevenson on the theme of her keynote address at the ACC.19.

Discover: Dr. Stevenson, you were asked to deliver the Chatterjee lecture at the American College of Cardiology 2019 conference. Who was Dr. Chatterjee and how did he impact the heart failure field?

Stevenson: Dr. Kanu Chatterjee was an extraordinary physician, humanist and clinical investigator in the field of heart failure. He died in 2015 at the age of 81. I am so grateful for the opportunity to have visited his clinic in San Francisco when I was just starting my career in heart failure and transplant at UCLA. He helped us to understand the pressures and flows that drive circulation during heart failure. In honoring his career, I mapped the journey that the field of heart failure has taken since those early days.

Discover: You were given the title “If We Start With Failure, How Can We Truly Succeed? My Vision for the Next 10 Years.” How is “failure” the starting point?

Heart failure was an accurate term decades ago, when most patients who came to us were expected to die within six months without transplantation. Over the 36 years I have been in the field, we have learned many lessons that have dramatically changed the outlook. Today, nearly 80 percent of patients under 70 who have heart failure without other major diseases are living five years after diagnosis. Most of the survivors are able to perform their daily activities and lead meaningful lives with work and family.

“Heart failure is now a needlessly grim term.”

Heart failure is now a needlessly grim term to describe a chronic diagnosis that, for most people, is about adapting to some limitations, but not to failure.

Discover: What has played the biggest role in this transformation?

Stevenson: Three major dimensions of change have led us into this new landscape. One is our progress in understanding that the congestion element of congestive heart failure is the central cause, not just of the symptoms of shortness of breath and leg swelling, but of worsening disease and death. We have made it a mission to reduce the build-up of pressure in and behind the heart and take the congestion out of heart failure.

The second is the mounting improvements in neurohormonal medication—the ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, and now angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs). These therapies have a cumulative and synergistic power to stabilize and improve the heart function.

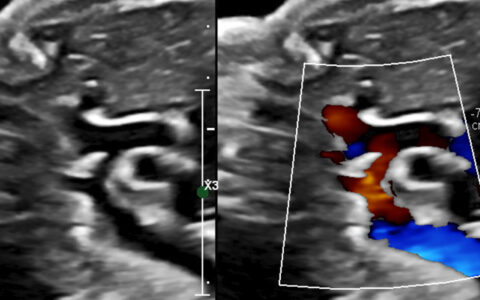

The third dimension is implanted devices that improve effectiveness of the heart, like the special pacemakers that resynchronize the heart. A newer device is the mitral valve clip that can be inserted with a catheter to help decrease the leaking of the valves that often develop in weakening hearts. This device was recently shown in the COAPT trial to improve symptoms and survival with heart failure and mitral regurgitation. At the ACC.19 meeting, we also saw new trial results demonstrating the dramatic impact of the implantable hemodynamic monitor that transmits heart pressures every day from home and guides therapy.

Discover: Why have haven’t you mentioned left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) or transplants among the game-changers?

Stevenson: Heart transplantation offers a life-saving miracle for those who are called to receive a donor heart, and Vanderbilt is one of the top two programs in the country for heart transplantation. We performed over 100 transplants last year, with outstanding results. LVADs also improve quality of life and survival for people who are severely limited by their heart failure. These benefits were confirmed in the two-year results from the Momentum III trial, although there are still many adverse events.

Most patients with advanced heart failure, however, have comorbidities that preclude LVAD or transplant, and we still have a shortage of donor hearts. Heart transplant is the answer to heart failure as the lottery is the answer to poverty. Only about 3,000 people have heart transplants each year now in the United States and about 4,000 have LVAD implants.

“Hope has to come from the hearts they have.”

For the majority of the six million people with heart failure, hope has to come from the hearts they have. Ironically, that hope has come largely from the lessons learned about heart failure at the transplant programs where there are always many more patients than donor hearts.

Discover: What cardiomyopathy innovations are you most involved in at Vanderbilt?

Stevenson: We were one of the early centers to use implantable heart pressure monitors and are excited that the latest results show reduction of heart failure hospitalizations by over half. They enable us to connect with our patients more often without them driving a long distance to appointments. A small sensor is implanted in a blood vessel in the lung to monitor pressures behind the heart, and patients transmit these pressures daily from home. Knowing these pressures helps us to guide their therapy and helps them to learn how to change their lifestyles to help keep them right in line.

It is much like how people with diabetes can measure their own glucose to adjust their insulin. It’s lifestyle-friendly, plus proactive in heading off problems and empowering the patient with more control over their condition.

I am also very excited about the new therapies to repair the mitral valve without surgery in patients with weak hearts. The challenge we still face is that most patients are not deriving optimal benefits from our therapies, due to limited insurance and access. This discourages patients and undermines their participation. Yet more and more, we understand just how vital patients’ investment in their own health is to stabilizing this disease.

Discover: Getting back to your core message, what disease do your patients have, if we don’t label it “heart failure”?

Stevenson: The stable condition can be called “cardiomyopathy,” a term that means disorder of the heart muscle. This would be accurate. I worry that the “heart failure” label discourages our young colleagues in medicine and nursing, whom we need to enter this field to advance it further. Just as no one wants to schedule an appointment in a “heart failure” clinic, who would aspire to grow up and go into a specialty of “failure”?

For patients with true heart failure, we offer the best place for transplants and mechanical assist devices. For the many other patients we follow whose hearts can continue, I would like to see this dark shadow of “failure” lifted away from their lives and the lives of their families.