Patients with recurrent episodes of ventricular tachycardia (VT) require therapy to suppress the arrhythmia, most commonly with antiarrhythmic drugs. Beta-blocker therapy is usually recommended and sotalol is an option for some patients. Chronic treatment with amiodarone is the most effective drug option and can reduce shocks from an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), but amiodarone has significant side effects that require careful monitoring.

“Unfortunately, there have been no major advances in antiarrhythmic drug therapy for over three decades,” said William Stevenson, M.D., director of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Clinical Research Program at Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute . “On the other hand, there have been substantial advances in the interventional technique of catheter ablation, which plays an increasingly important role in reducing or preventing recurrent episodes of sustained VT.”

Catheter Ablation Has Changed the Game

Catheter ablation requires localization of the area (usually a scar) causing the arrhythmia and damaging the area by burning it with radiofrequency current. Procedure effectiveness is influenced by the location of the arrhythmia substrate, which varies with the type of heart disease. The procedural risks, which are similar to those of other heart catheterization procedures, must be weighed against the potential benefits.

For patients with recurrent arrhythmia, catheter ablation may be the best option.

“ICDs provide an effective safety net for managing ventricular tachycardias in many patients who have associated heart disease, especially those with co-morbidities,” said Stevenson, “but many other patients continue to have recurrent episodes of arrhythmia. For them, catheter ablation is often the best option for controlling the arrhythmia and preventing ICD shocks.”

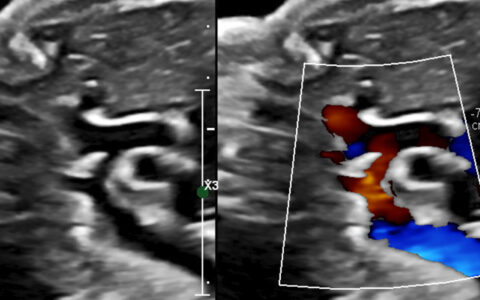

The ability to target the area of ventricular scarring has been greatly improved by mapping systems that provide three-dimensional representation of cardiac anatomy in relation to the electrical abnormalities. A combination of epicardial mapping and catheter ablation is now commonly performed in experienced centers after failed endocardial VT ablation, and in some types of cardiomyopathy. More advanced ablation approaches required for some patients include transcoronary ethanol ablation and ablation at open heart surgery.

Needle Ablation for Hard-to-Reach Arrythmia-Causing Scars

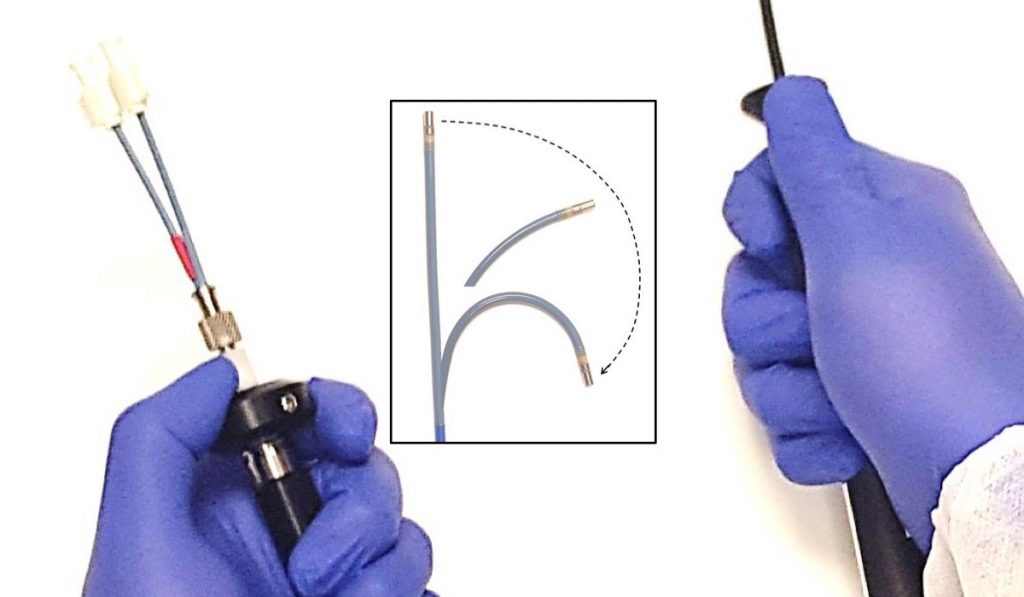

When endocardial and epicardial catheter ablation fail to control the arrhythmia, the problem is often arrhythmia substrate located within the ventricular wall. One new treatment that Stevenson is investigating is an irrigated needle ablation catheter. This catheter allows a 27-gauge needle to be extended into the ventricular wall to reach intramural scars requiring ablation.

“In order to reach the scarring that is deep within the heart muscle—where it cannot be reached from the inside or outside surface of the heart—this device includes a needle that is inserted through the heart wall into the abnormal area,” Stevenson explained. “The needle is so small that if you apply current to it, only a very small area is heated, making a very small lesion just along the track of the needle.” To increase the area ablated, saline is irrigated through the needle and distributes through the tissue, facilitating the dispersion of the electrical current.

Stevenson started developing the catheter several years ago and Vanderbilt is one of only four centers in the world (three with FDA permission in the U.S.) to use it with patients who have failed other options. In 2019, investigators from these centers plan to publish a study outlining results in the first 31 patients.

“Twenty to fifty percent of patients who are referred to us after failing attempts at catheter ablation have areas of substrate that are difficult to reach,” said Stevenson. “I am optimistic that this tool will help many patients who have difficult-to-control VT.”