When Cirris and Matthew Hatfield first brought their newborn daughter to the Vanderbilt Eye Institute (VEI), baby Athena had cloudy corneas – and poor, if any, vision.

After being seen by Vanderbilt pediatric ophthalmologists, Athena was prescribed three glaucoma medications to relieve the pressure in her eyes, and her parents were told their baby would need surgery – soon – to have any hope of sight.

Today, Athena is a thriving 10-year-old who is reading and attending regular school after bilateral optical iridectomies to treat her severe anterior segment dysgenesis (ASD).

A variety of genes are involved in the eye’s anterior segment development, and ASD comprises a diverse group. Athena was diagnosed with Peters Anomaly, which is very rare, with only 44–60 annual cases reported in the U.S.

“When I first saw Athena, she was 6 days old,” said Karen Joos, M.D., Ph.D., who specializes in the management of glaucomatous diseases in children and adults. “She was sent to me with elevated pressure. After a discussion with her parents, I added an oral glaucoma medication to try to further reduce the pressure.”

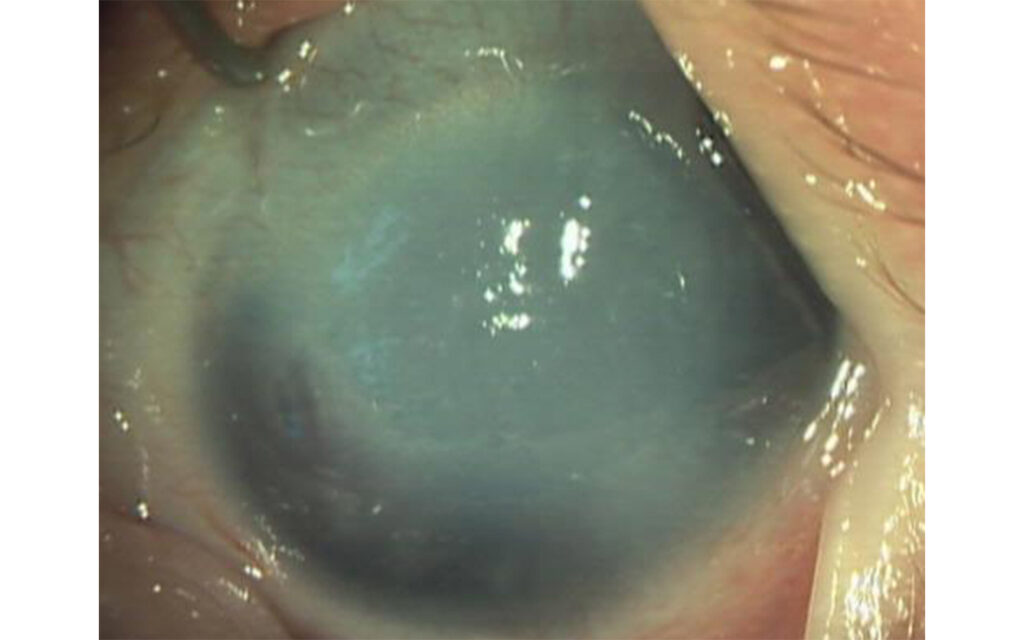

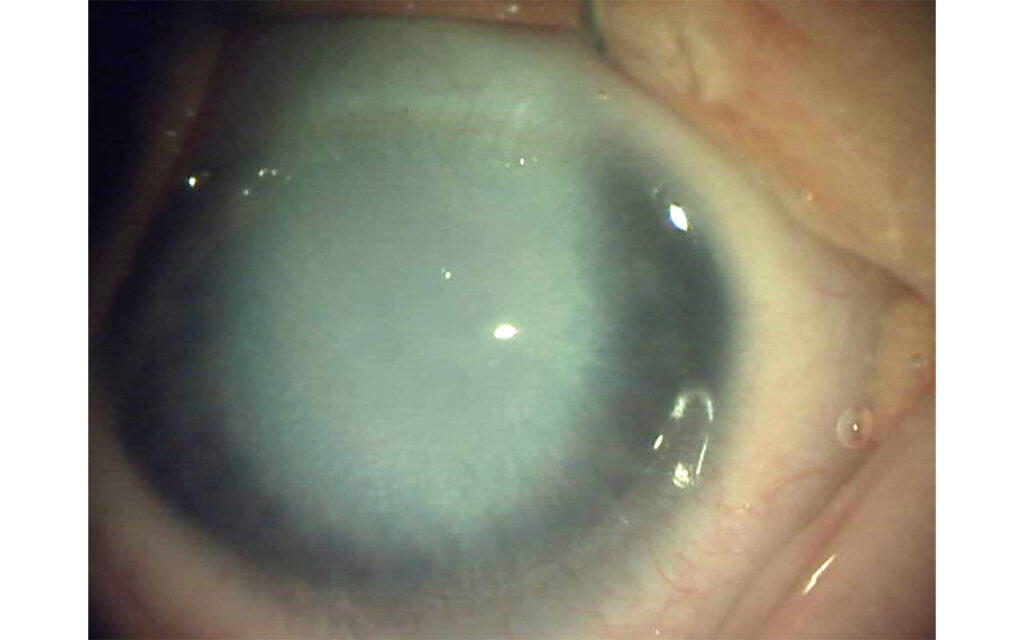

At 2½ weeks, Athena underwent anesthesia while her eyes were examined by Joos and a VEI cornea colleague. They found she had corneal opacification, microcornea vascularization with extensive iris adhesions to the inner cornea, and a shallow anterior chamber in both eyes.

“Her pressures were better, but her corneas were very thick,” Joos said.

Corneal transplant has been the standard treatment for ASD, but the failure rate is high – up to 70 percent, in good circumstances. Seeking a better solution, Joos recommended optical iridectomy, an alternative approach when corneal transplant cannot be performed.

Performed on adults since the 1800s, optical iridectomy creates a hole in the iris to allow an alternative clearer light path in cases where central corneal opacities obstruct the pupil.

“We were very torn about what to do and spent several sleepless nights doing research about the procedure,” said Athena’s mom. “We knew that with a corneal transplant, the recovery would take longer and that she would have to have the surgery multiple times as the eyes grew.”

The parents sought additional opinions from two pediatric cornea specialists, who confirmed that corneal transplant was not an option. They returned to Vanderbilt Eye Institute, where Joos performed bilateral inferotemporal optical iridectomies.

Giving Athena a Chance

In Athena’s case, the objectives of the surgery were twofold: to deepen the anterior chamber and sever some of the adhesions to improve pressure; and to position the iridectomy and make it large enough to allow light to enter the retina, offering a chance for some vision to develop.

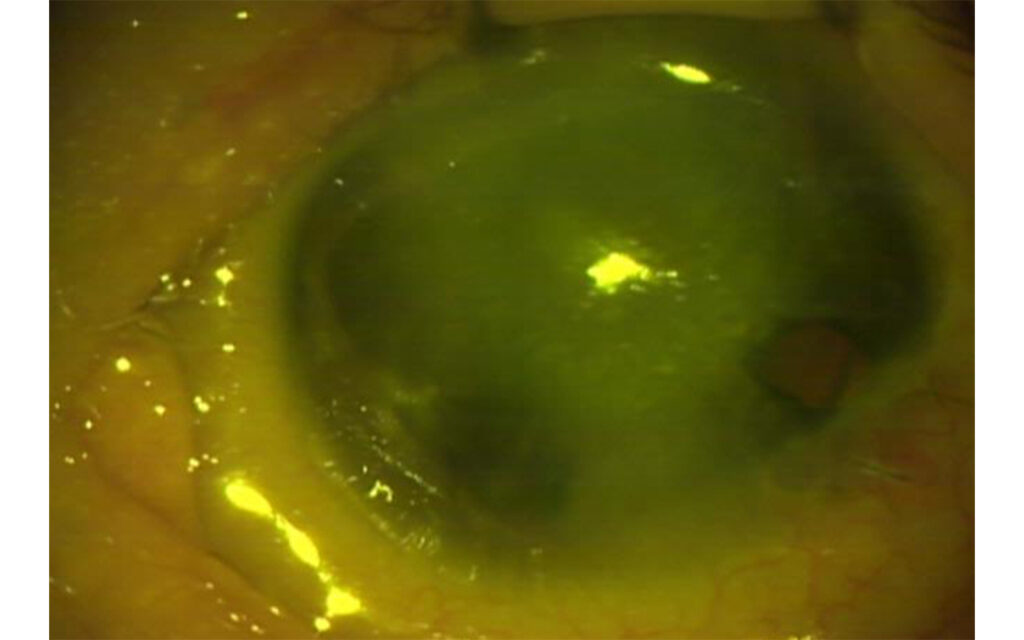

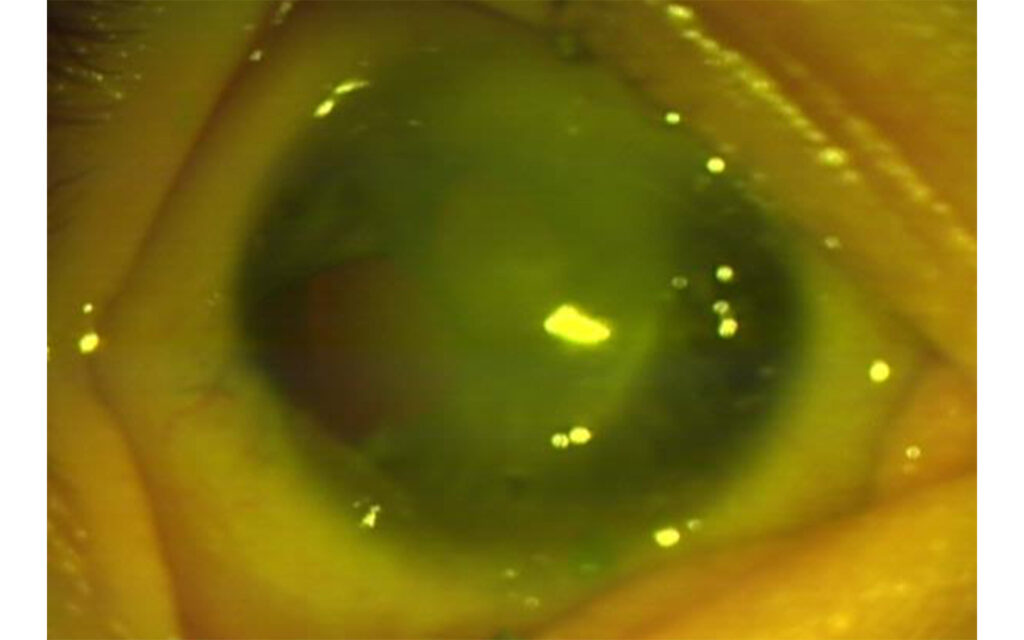

“The technique is to open the sclera where it meets the cornea and remove more iris than is performed for a glaucoma iridectomy,” Joos said. “Athena’s opacity was central, so the iridectomy was made where the cornea was clearer and light would not be blocked by an eyelid.”

At her 2½ months postoperative visit, Athena’s corneas had cleared remarkably, and the pressure was reduced using two glaucoma medicines. Five percent sodium chloride drops also were administered to help with the clearing.

Signs of fine vision were slow to emerge, beginning about age 2. “We were starting to get discouraged,” Cirris said.

But one day, as Matthew held up a piece of yarn and waved it in front of their daughter’s face, Athena reached out to try and catch it. He excitedly called Cirris at work to relay the good news.

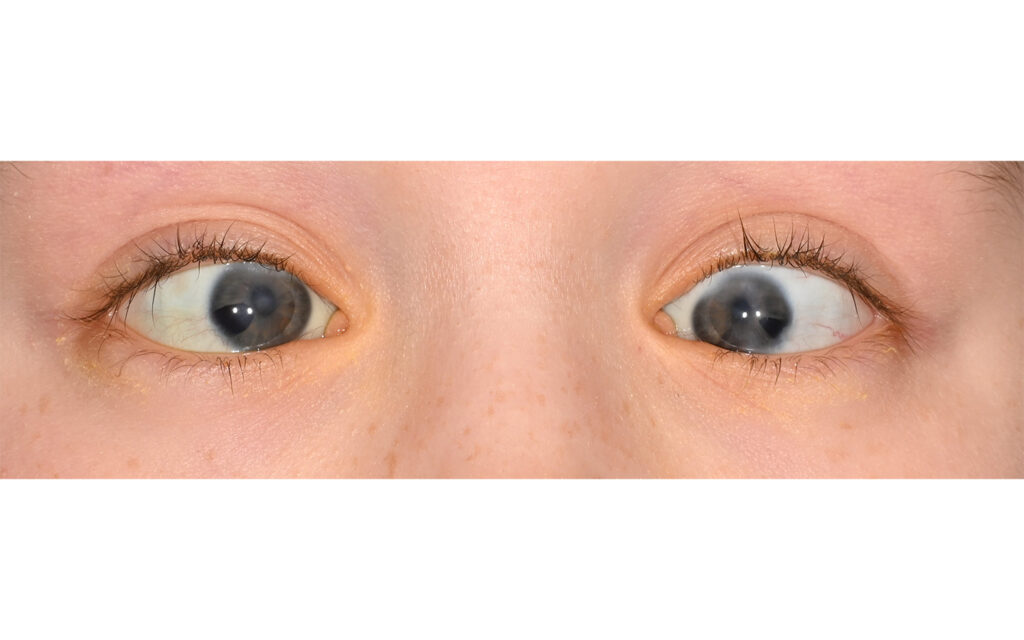

“Athena really had a great result: the corneas have continued to clear over time. When you look at her eyes now the optical iridectomies look almost like regular pupils.”

“From that point on, we were extremely encouraged and were delighted in the ways in which Athena demonstrated her ability to see even small objects,” she said. “Numbers and letters quickly became her best friends.”

Joos described the procedures as having “a really great result” for Athena.

“The corneas have continued to clear over time,” Joos said. “Her vision is now 20/100 in both the right and the left eye, and the eyes open together are 20/70. Pressures are controlled with one glaucoma medicine. When you look at her eyes now – especially in photographs – the optical iridectomies look almost like regular pupils.”

Beyond Baby Steps

Joos continues to follow Athena’s progress both inside and outside the clinic. Today, the plucky pre-teen is reading and going to regular school.

“Athena’s life today is just like that of most kids her age,” her mother said. “She’s very social and has lots of friends. If you saw her on the playground, you would think she had normal vision – she’s out there kicking the ball with everyone else!”

“Our goal is always to prevent blindness. Athena is just one example of what can be accomplished with early intervention and treatment.”

The family lives in Kentucky and has taken advantage of every program the state offers. Kentucky First Steps and a Head Start program for developmental delays provided preschool help. In elementary school, Athena receives vision and speech therapy, has an interpretive aide, and uses a magnifying device provided by the Kentucky School for the Blind.

Cirris Hatfield cannot express enough gratitude for VEI and the compassionate care Athena continues to receive. “Athena loves Dr. Joos, and I completely trust her with her care.”

A decade ago, when Joos first saw Athena, optical iridectomy was a largely untested approach in children with anterior segment dysgenesis. Since Athena’s surgery, Joos has performed about a dozen optical iridectomies on children with ASD.

“Our goal is always to prevent blindness,” she said. “Athena is just one example of what can be accomplished with early intervention and treatment.”