Frontotemporal lobe dementia hits early and fast, striking 60 percent of its victims between the ages of 45 and 65 before making a speedy progression. Though diagnoses remain rare, it is considered the most common cause of dementia for people under age 60.

Ryan Darby, M.D., a specialist in neurodegenerative disorders, founded the Frontotemporal Lobe Dementia Clinic at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in 2017 to provide evaluation and treatment – the first dedicated frontotemporal lobe dementia (FTLD) center in the Southeast.

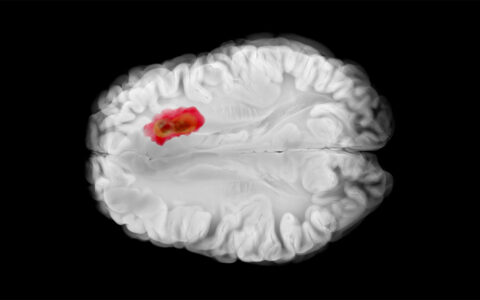

Characterized on imaging by shrinkage in the brain’s frontotemporal lobe, symptoms of FTLD are distinct from other forms of dementia, and its protein deposits differ from those of Alzheimer’s disease. Average survival length is 7.5 years after diagnosis.

“The driving force of the clinic is not only what we can offer now, but what opportunities we can provide patients to participate in research that might advance treatment in the future,” Darby said.

FTLD Development

In about 10 percent of cases, FTLD has a genetic association.

“There are known mutations in about 20-30 identified genes which dictate that the individual will develop the disease at some point in time,” Darby said. “However, in 30 to 40 percent of cases there is a family history, but no known genetic mutation.

“In genetic cases, we know some of the pathways that are leading to the accumulation of these proteins. In cases where there is no genetic association, however, those pathways are still unclear.”

There are two main types of protein deposits we see – one is tau and the other is TDP43.

Confounding Behaviors

People in the early stages of FTLD display prominent changes to personality and behavior in ways that may be misidentified as a psychiatric disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or even a midlife crisis. Those changes are often accompanied by changes in motor control demonstrated through as loss of coordination and even falls. Language complications are also frequent manifestations.

Many of these symptoms mimic those of more common diseases – chiefly psychiatric disorders, Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s – as well as some rare neurological diseases, like Huntington’s.

Ultimately, an evaluation will yield distinctions from psychiatric disorders or other neurodegenerative brain diseases. For example, while memory loss is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, FTLD patients experience loss of language and executive function, leading to impulsivity, disinhibition, inappropriate social behaviors, and lack of empathy.

“We look at clues, like symptoms of bipolar disorder cropping up in someone in their 40s as opposed to their 20s, which is relatively unusual,” Darby said. “But it typically takes a while before symptoms lead people to an evaluation for frontotemporal lobe dementia.”

Managing Symptoms

Psychiatric medications can help mitigate some of the behavioral symptoms but do not slow progression of the disease. In situations where language is affected, speech therapy is a commonly used tool.

Vanderbilt’s FTLC clinic has teamed up with other centers around the country in a longitudinal cohort study funded by the NIH. Its goal is to determine a path to best practices for identifying chief biomarkers, measuring and predicting symptoms and tracking progression over time.

Today’s patients, Darby said, who receive care through a dedicated clinic benefit from optimized and meaningful support and cutting-edge treatment for people with this heterogenous set of symptoms.

“We do yearly comprehensive visits with patients and families that involve working with neurologists, psychiatrists, neuropsychiatrists, and genetic counselors,” he said. “We test genetics, blood and spinal fluid, perform MRIs, and provide resources, from social workers to speech therapists. So really, it is a whole gamut of services. Importantly, the clinic staff can connect patients with the most promising clinical trials.”

Corralling Technologies

Some research suggests the disease may spread through neural tracts to different parts of the brain. Investigations into noninvasive brain stimulation are holding promises for treatment using methods such as s transcranial magnetic stimulation or electrical stimulation.

“Although there is no clear evidence yet, the possibility of modifying functional activity in certain parts of the brain could change that progression,” Darby said. “These modalities are thought to have the most potential to improve language function, but researchers are also hoping to discover an impact on behavioral problems as well, through selectively stimulating certain locations in the brain.”

Other researchers are investigating biological interventions to alter the proteins found in patients with FTLD. The quest to identify tau in the brain is being spurred on though clinical trials on patients with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), Darby said.

“Tau is present in only about half of people with FTLD, but the hope is that they may also identify other proteins, like TDP-43, in the process, something that crosses over to FTLD research.”

Other clinical trials are focused on the genetic form of FTLD, with the prospect of modifying the known gene’s function through viral gene replacement or by targeting the biological pathway initiated by that gene.

“The hope is that we can inject an adeno-associated viral vector into the brain or spinal fluid to introduce a normal copy of the gene that would then duplicate that gene in healthy cells,” Darby said.