A relatively new and effective method to support smoking cessation received FDA approval in 2020, yet is only now being studied in a population known for disproportionate tobacco use: people with schizophrenia.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center is launching an investigation into whether repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) can reduce nicotine cravings in adults with schizophrenia – a group that experience exceptionally high rates of smoking and smoking-related illness.

“Nicotine is clearly helping people with these disorders in lots of different ways. We want to figure out how and why.”

“Across all psychiatric disorders, there is a higher prevalence of nicotine use than in the general population,” said Heather Burrell Ward, M.D., director of neuromodulation research at Vanderbilt. “Nicotine is clearly helping people with these disorders in lots of different ways. We want to figure out how and why.”

Noninvasive, Nonpharmaceutical

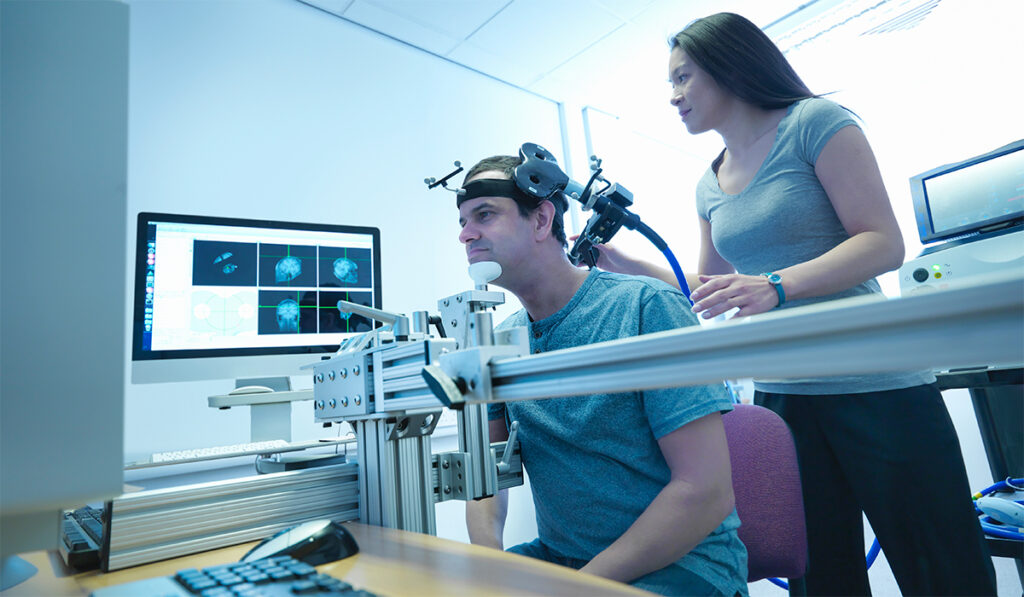

The FDA’s approval of the treatment recognized benefits of using rTMS – applied to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex – to reduce cigarette consumption and cravings in smokers.

The noninvasive treatment with few side effects uses magnetic fields to influence brain activity. An electromagnetic coil is positioned on the patient’s scalp, and current is pulsed through the coil. This generates a magnetic field that affects the firing of neurons in the brain.

Ward recently was awarded nearly $1 million in funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse for a five-year trial to see if rTMS works to reduce nicotine cravings in people with schizophrenia, while also mimicking the perceived benefits of nicotine.

3 Times More Common

The high prevalence of nicotine use among people with schizophrenia is three times that of the general population, averaging between 60 and 90 percent, Ward explained.

“We also know that treatments for smoking cessation are significantly less effective in people with schizophrenia, all of which suggests that maybe the brain circuitry driving nicotine use in an otherwise healthy person is different in someone with schizophrenia,” she said.

Before the current trial, Ward and her colleagues examined the brain for circuitry that might be implicated in high nicotine use among people with schizophrenia.

“We used computational methods to ask if there was an area of the brain that was related to cigarette use,” she said. “Doing that, we observed that the default-mode network was related to cigarette use in people with schizophrenia – but not in healthy people.”

They established that nicotine normalizes hyperactivity in the brains of people with schizophrenia.

“Hyperactivity in the default-mode network is associated with impaired cognition and deficits in attention and working memory,” she said.

An anatomically interconnected structure, one of several in the brain that appear to function together systematically, the default mode is a resting-state brain network that becomes active when a person is not engaging with the external environment, including during periods of introspection and physical self-regard, Ward said.

Importantly, the default-mode network has also been linked to craving and to cognitive performance. Apparently, nicotine helps people with schizophrenia think more clearly.

“If abnormal activity is associated with cognitive impairment and nicotine is normalizing the network’s activity, the next challenge is to find something else to reduce the hyperactivity, something that’s not nicotine.”

Looking for Change

Today’s primary medical treatments for schizophrenia are largely composed of antipsychotic medication, which do not improve cognition and often have serious side effects, Ward said.

“Current medications help with certain types of symptoms, hallucinations and delusions, but they’re not helpful when it comes to cognitive impairment,” Ward said. “It makes perfect sense that people are drawn to nicotine to help with cognitive performance.”

“Many people with psychiatric disorders really do want to quit smoking.”

In the new trial, Ward will focus on adult smokers with schizophrenia who will undergo a five-day rTMS intervention targeted to the default-mode network, allowing the researchers to examine patterns of connectivity and track changes in cravings.

“We know that five sessions are not enough to get people to quit,” Ward said. “Our goal is to find out if we see a hint of a change. If cravings go down and we see changes in the default-mode network, that is good evidence that we should scale this up for smoking cessation.”

Statistics show that people with schizophrenia die 20 years earlier than the general population, largely due to tobacco use, Ward said.

“Many people with psychiatric disorders really do want to quit smoking, and we can help.”

Tobacco smoking was adopted in Europe after being imported from America. Initially, it was considered it a medicinal herb offering many benefits.

“Over a dozen books published around the middle of the 16th century mention tobacco as a cure for everything from pains in the joints to epilepsy to plague,” according to a National Park Service history of tobacco’s role in Virginia. Today, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control reports cigarette smoking can be linked to more than 480,000 deaths annually in the United States – or one in five – and is considered to be the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the country.