While researchers continue their relentless march towards a cure for Huntington’s disease (HD), experts are also seeking ways to reach patients earlier in the disease’s progression.

Evidence is mounting that psychiatric and behavioral HD symptoms can begin years before the motor symptoms that typically trigger the diagnosis.

HD is a progressive and devastating neurological condition caused by a heritable single-allele mutation that creates an expanded repeat of the CAG (cytosine, adenine and guanine) trinucleotides. A parent who has the gene has a 50 percent chance of passing it to their children.

In large part, the length of the abnormally expanded CAG influences the age of symptom onset, disease severity, and pace of progression, said Daniel Claassen, M.D., chief of the Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology Division and director of the Huntington’s Disease and Chorea Clinic at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Claassen is calling for earlier recognition of these symptoms, urging neurologists, social workers and research scientists at the Southeast Regional Huntington’s Disease Symposium in February of 2023 to identify and treat patients with symptoms that fall outside the motor realm.

“We know now that symptoms like impulsivity, aggression, manic behavior, apathy, cognitive impairment, and depression can manifest before chorea or other motor symptoms. Lives can quickly unravel when these are unaddressed or misdiagnosed,” Claassen said.

“Today, with state-of-the-art therapies, which include medications and counseling, we can go a long way toward helping avoid this consequence – if clinicians know what to look for and how to proceed.”

Early Recognition Warranted

About 75,000 people in the U.S. carry the HD gene, and over a third of those carriers manifest symptoms. Though efforts to impede progression of the disease have not yet been realized, significant progress is being made in developing drugs to help with motor symptom control and reduce discomfort.

Genetic testing is needed to confirm, but clinical diagnosis is based on assessment of symptoms, which have traditionally been spasmodic movements, known as chorea. Claassen says we can now do more for both those who have tested positive and those who are untested but at risk due to a parent with the HD gene.

“We are understanding more and more about early cognitive and psychiatric symptoms,” Claassen said. “We need to ask, ‘Has the change been persistent over time? Have there been consequences, such as poor grades, loss of a job, harmed relationships, trouble with the law?’

“The clinician can make a diagnosis based on these non-motor symptoms so the patient can receive treatment and, in many cases, qualify for disability benefits.”

HD and Early Therapy

Joshua R. Smith, M.D., a Vanderbilt child psychiatrist who focuses on neurological diseases, has seen firsthand how today’s psychiatric medications can help children with juvenile or childhood HD and a related mental illness.

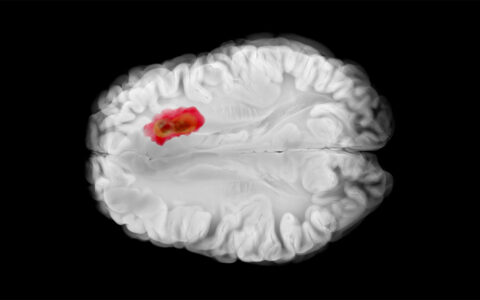

“Case reports of juvenile- or childhood-onset patients as young as eight years have shown atrophy of caudate nuclei and putamen, so It makes sense that some of these children are displaying cognitive and behavioral changes,” he said.

“In children, it can be heard to sort out what is and is not within the normal range of developmental behaviors. We need to be on the lookout for the aberrations that persist and ask ourselves what may be in play: HD, family dynamics, or something else?”

While genetic testing is not normally recommended for minors, Claassen says concerning behavioral patterns or motor symptoms may help confirm a diagnosis. Then, the clinician can treat these symptoms within the context of HD progression.

“Early care for young patients with juvenile and pediatric Huntington’s disease, as well as older patients who manifest known behavioral symptoms, not only provides help in managing their lives today, but provides a safer bridge to a time when a cure is available,” Claassen said.

On the Radar

Children, adolescents and young adults can easily fly under a clinician’s radar because HD is commonly thought to present in midlife. It can be a long road from primary care physician to a psychiatrist or neurologist – each perhaps considering it the other’s wheelhouse – and on to an HD clinic.

“A surprising number of families don’t even know they have the gene,” he said. “People may recall an uncle who ‘seemed to be irritable’ but they never knew why. While the luxury of time is seldom ours, I urge health care teams to ask open-ended questions about the family history when a patient presents with behavioral and life changes, and follow up when they see personal or family dysfunction that might fit a pattern for HD.”

Seeking a Cure

Research toward a cure focuses mostly on targeting the mutant huntingtin (mHtt) gene and the proteins it produces. One current study is testing direct delivery into the brain of genetic modification through adeno-associated viruses to stop mHtt transcription. However, this and other research trajectories will likely take many years before they are FDA-approved and available to patients.

A small but growing number of couples who know they are at risk for HD are using in vitro fertilization (IVF) to select embryos that are free of the HD-gene. While some philanthropists are now awarding grants to cover the costs of one or two IVF attempts, insurance coverage of this expense would provide significant fuel for extending the option to more couples.