For 20 years, nephrologist William F. Fissell, M.D., of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and his collaborators have had their minds set on a moonshot. “Our end goal is a bioengineered, mass-produced, universal-donor kidney to overcome the scarcity problem in kidney transplant, full stop,” says Fissell, who is also an associate professor of biomedical engineering and co-directs The Kidney Project with Shuvo Roy, Ph.D., of University of California San Francisco.

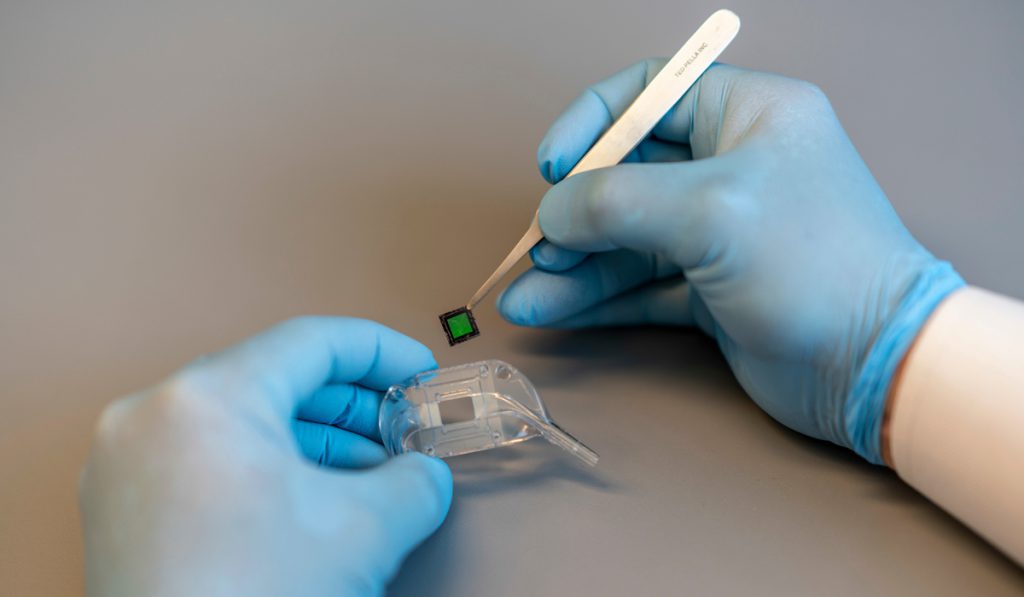

Where that project stands today is a prototype artificial kidney that could merge two revolutionary innovations. The proposed hardware component is a fully implantable dialyzer with a microchip-sized filter that Fissell borrowed conceptually from his earlier career in astronomy. A second component is a living cell “bioreactor” to endow the implantable kidney with healthy transport and metabolic functions.

In April, The Kidney Project’s implantable dialysis unit was chosen among 15 entries nationally to advance in the Kidney Innovation Accelerator, or KidneyX, prize completion “Redesign Dialysis.” The competition is one of the first initiatives of the KidneyX program, a joint effort of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and American Society of Nephrology (ASN) to spur innovation in renal disease treatments.

The KidneyX Prize

The Redesign Dialysis prize competition aims to encourage “disruptive” new technologies and attract outside inventors and investors. Fissell hopes it will shake up a longstanding stagnancy in the dialysis toolkit. “The goal of KidneyX is to create a broad tent—to create buzz to attract people from outside the field who had never thought about dialysis, whether they are coming from aerospace, from chemical engineering or from pharmaceuticals.”

“The goal of KidneyX is to create a broad tent—to create buzz to attract people from outside the field who had never thought about dialysis.”

Fissell says the true value of the prize competition far exceeds the $75,000 award given to the 15 teams that advanced into Phase II. He is grateful to the ASN and its membership for stepping up to fund the prize, but he is most excited by KidneyX’s gesture of federal support for dialysis innovators to take an entrepreneurial approach.

“Take our device, for example. If we need to scale up to produce that 1-by-1-centimeter filtration chip by getting a silicon plant in South Korea, importing our processes and generating 50,000 units of incredibly precise devices at very high yield, that takes investment and expertise from outside the hypothesis-testing science that is the purview of the NIH,” Fissell said.

Reinventing Hemodialysis

Today, home dialysis faces a host of challenges. Offering a device to radically simplify home hemodialysis could lower one major barrier: the daunting patient experience of using current systems. In addition, making it easier and more appealing to dialyze frequently would align with the evidence showing benefits increase with more intensive sessions.

“The current morbidity of end-stage renal disease treated with dialysis is really an epiphenomenon of how we apply the machine,” Fissell says. “Colleagues in Canada have shown, I think pretty conclusively, that if you dialyze patients eight hours a night every night, essentially a miracle happens. Patients can eat what they want; they come off their blood pressure pills; their cardiac stress resolves; their hearts remodel in a healthy way.”

Fissell and his team are racing toward a true artificial kidney—one that would filter waste constantly like a healthy organ. If their implantable dialyzer technology can be coupled with their cellular “bioreactor,” it could one day offer patients just such a solution.

“We still have our eyes on the prize,” Fissell says. “As an interim goal, we hope we can reengineer dialysis—the goal of the first round of KidneyX prize competition—to break the in-center, intermittent model and make it more palatable for patients to dialyze at home.”